GRIT Ransomware Report: May 2024

Additional contributors to this report: Grayson North, Jason Baker May 2024 closed with an increase in overall victim volume, though […]

The post GRIT Ransomware Report: May 2024 appeared first on Security Boulevard.

Additional contributors to this report: Grayson North, Jason Baker May 2024 closed with an increase in overall victim volume, though […]

The post GRIT Ransomware Report: May 2024 appeared first on Security Boulevard.

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

If you’ve ever been to Taiwan, you’ve likely run into Gogoro’s green-and-white battery-swap stations in one city or another. With 12,500 stations around the island, Gogoro has built a sweeping network that allows users of electric scooters to drop off an empty battery and get a fully charged one immediately. Gogoro is also found in China, India, and a few other countries.

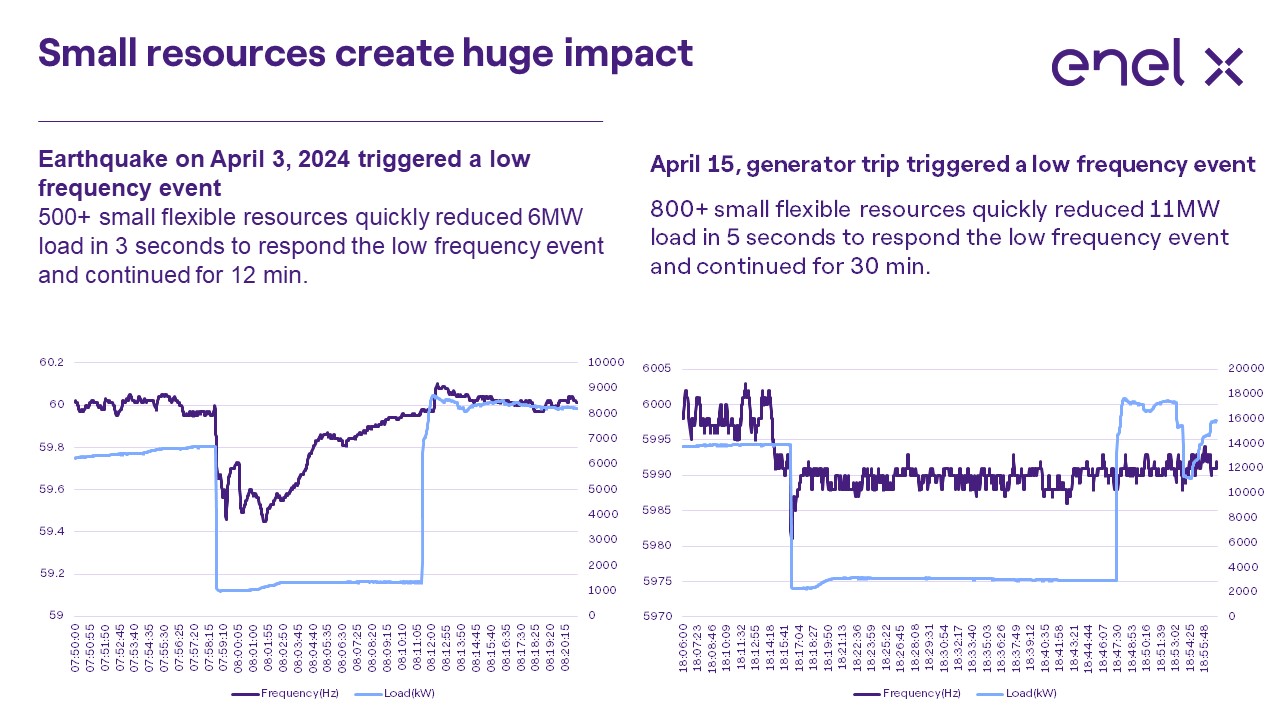

This morning, I published a story on how Gogoro’s battery-swap network in Taiwan reacted to emergency blackouts after the 7.4 magnitude earthquake there this April. I talked to Horace Luke, Gogoro’s cofounder and CEO, to understand how in three seconds, over 500 Gogoro battery-swap locations stopped drawing electricity from the grid, helping stabilize the power frequency.

Gogoro’s battery stations acted like something called a virtual power plant (VPP), a new idea that’s becoming adopted around the world as a way to stitch renewable energy into the grid. The system draws energy from distributed sources like battery storage or small rooftop solar panels and coordinates those sources to increase supply when electricity demand peaks. As a result, it reduces the reliance on traditional coal or gas power plants.

There’s actually a natural synergy between technologies like battery swapping and virtual power plants (VPP). Not only can battery-swap stations coordinate charging times with the needs of the grid, but the idle batteries sitting in Gogoro’s stations can also become an energy reserve in times of emergency, potentially feeding energy back to the grid. If you want to learn more about how this system works, you can read the full story here.

When I talked to Gogoro’s Luke for this story, I asked him: “At what point in the company’s history did you come up with the idea to use these batteries for VPP networks?”

To my surprise, Luke answered: “Day one.”

As he explains, Gogoro was actually not founded to be an electric-scooter company; it was founded to be a “smart energy” company.

“We started with the thesis of how smart energy, through portability and connectivity, can enable many use case scenarios,” Luke says. “Transportation happens to be accounting for something like 27% or 28% of your energy use in your daily life.” And that’s why the company first designed the batteries for two-wheeled vehicles, a popular transportation option in Taiwan and across Asia.

Having succeeded in promoting its scooters and the battery-swap charging method in Taiwan, it is now able to explore other possible uses of these modular, portable batteries—more than 1.4 million of which are in circulation at this point.

“Think of smart, portable, connected energy like a propane tank,” Luke says. Depending on their size, propane tanks can be used to cook in the wild or to heat a patio. If lithium batteries can be modular and portable in a similar way, they can also serve many different purposes.

Using them in VPP programs that protect the grid from blackouts is one; beyond that, in Taipei City, Gogoro has worked with the local government to build energy backup stations for traffic lights, using the same batteries to keep the lights running in future blackouts. The batteries can also be used as backup power storage for critical facilities like hospitals. When a blackout happens, battery storage can release electricity much faster than diesel generators, keeping the impact at a minimum.

None of this would be possible without the recent advances that have made batteries more powerful and efficient. And it was clear from our conversation that Luke is obsessed with batteries—the long way the technology has come, and their potential to address a lot more energy use cases in the future.

“I still remember getting my first flashlight when I was a little kid. That button just turned the little lightbulb on and off. And that was what was amazing about batteries at the time,” says Luke. “Never did people think that AA batteries were going to power calculators or the Walkman. The guy that invented the alkaline battery never thought that. We’ll continue to take that creativity and apply it to portable energy, and that’s what inspires us every day.”

What other purposes do you think portable lithium batteries like the ones made by Gogoro could have? Let me know your ideas by writing to zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. Far-right parties won big in the latest European Parliament elections, which could push the EU further toward a trade war with China. (Nikkei Asia $)

2. Volvo has started moving some of its manufacturing capacity from China to Belgium in order to avoid the European Union tariffs on Chinese imports. (The Times $)

3. Some major crypto exchanges have withdrawn from applying for business licenses in Hong Kong after the city government clarified that it doesn’t welcome businesses that offer crypto services to mainland China. (South China Morning Post $)

4. NewsBreak, the most downloaded news app in the US, does most of its engineering work in China. The app has also been found to use AI tools to make up local news that never happened. (Reuters $)

5. The Australian government ordered a China-linked fund to reduce its investment in an Australian rare-earth-mining company. (A/symmetric)

6. China just installed the largest offshore wind turbine in the world. It’s designed to generate enough power in a year for around 36,000 households. (Electrek)

7. Four college instructors from Iowa were stabbed on a visit to northern China. While the motive and identity of the assailant are still unknown, the incident has been quickly censored on the Chinese internet. (BBC)

Qian Zhimin, a Chinese businesswoman who fled the country in 2017 after raising billions of dollars from Chinese investors in the name of bitcoin investments, was arrested in London and is facing a trial in October this year, according to the Chinese publication Caijing. In the early 2010s, when the cryptocurrency first became known in China, Qian’s company lured over 128,000 retail investors, predominantly elderly people, to buy fraudulent investment products that bet on the price of bitcoins and gadgets like smart bracelets that allegedly could also mine bitcoins.

After the scam was exposed, Qian escaped to the UK with a fake passport. She controls over 61,000 bitcoins, now worth nearly $4 billion, and has been trying to liquidate them by buying properties in London. But those attempts caught the attention of anti-money-laundering authorities in the UK. With her trial date approaching, the victims in China are hoping to work with the UK jurisdiction to recover their assets.

I know one day we will see self-driving vehicles racing each other and cutting each other off, but I didn’t expect it to happen so soon with two package delivery robots in China. Maybe it’s just their look, but it seems cuter than when human drivers do the same thing?

TBH, I was expecting a world where unmanned delivery vehicles racing each other on busy streets to come maybe 5 yrs from now, but JD & its subsidiary Dada are making it happen w/o hitting anything

— tphuang (@tphuang) June 9, 2024

RIP to China's delivery ppl pic.twitter.com/Ae1Wy4mWAj

Not our fault, says CISO: “UNC5537” breached at least 165 Snowflake instances, including Ticketmaster, LendingTree and, allegedly, Advance Auto Parts.

The post Ticketmaster is Tip of Iceberg: 165+ Snowflake Customers Hacked appeared first on Security Boulevard.

In the ever-evolving landscape of cyberthreats, email remains a prime target for malicious actors, with zero-hour Business Email Compromise (BEC) and advanced phishing attacks posing significant risks to organizations. A recent independent study by The Tolly Group, commissioned by SlashNext, highlights the company’s Gen AI powered Integrated Cloud Email Security (ICES) solution, demonstrating its superior […]

The post The Tolly Group Report Highlights SlashNext’s Gen AI-Powered Email Security Prowess first appeared on SlashNext.

The post The Tolly Group Report Highlights SlashNext’s Gen AI-Powered Email Security Prowess appeared first on Security Boulevard.

Enlarge / The fourth full-scale test flight of SpaceX's Starship rocket took off from Starbase, the company's privately-owned spaceport near Brownsville, Texas.

Welcome to Edition 6.47 of the Rocket Report! The monumental news of late is that Boeing's Starliner spacecraft not only successfully launched on an Atlas V rocket, but then subsequently docked with the International Space Station. Congratulations to all involved. It's been a long road to get here.

As always, we welcome reader submissions, and if you don't want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Firefly lands massive launch contract. Firefly Aerospace announced Wednesday that it has signed a multi-launch agreement with Lockheed Martin for 25 launches on Firefly’s Alpha rocket through the end of this decade. This agreement commits Lockheed Martin to 15 launch reservations and 10 optional launches. Alpha will launch Lockheed Martin spacecraft into low-Earth orbit from Firefly’s facilities on the West and East Coast. The first mission will launch on Alpha flight 6, from Firefly’s SLC-2 launch site at the Vandenberg Space Force Base later this year.

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

Have you ever thought about the miraculous fact that despite the myriad differences between languages, virtually everyone uses the same QWERTY keyboards? Many languages have more or fewer than 26 letters in their alphabet—or no “alphabet” at all, like Chinese, which has tens of thousands of characters. Yet somehow everyone uses the same keyboard to communicate.

Last week, MIT Technology Review published an excerpt from a new book, The Chinese Computer, which talks about how this problem was solved in China. After generations of work to sort Chinese characters, modify computer parts, and create keyboard apps that automatically predict the next character, it is finally possible for any Chinese speaker to use a QWERTY keyboard.

But the book doesn’t stop there. It ends with a bigger question about what this all means: Why is it necessary for speakers of non-Latin languages to adapt modern technologies for their uses, and what do their efforts contribute to computing technologies?

I talked to the book’s author, Tom Mullaney, a professor of history at Stanford University. We ended up geeking out over keyboards, computers, the English-centric design that underlies everything about computing, and even how keyboards affect emerging technologies like virtual reality. Here are some of his most fascinating answers, lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Mullaney’s book covers many experiments across multiple decades that ultimately made typing Chinese possible and efficient on a QWERTY keyboard, but a similar process has played out all around the world. Many countries with non-Latin languages had to work out how they could use a Western computer to input and process their own languages.

Mullaney: In the Chinese case—but also in Japanese, Korean, and many other non-Western writing systems—this wasn’t done for fun. It was done out of brute necessity because the dominant model of keyboard-based computing, born and raised in the English-speaking world, is not compatible with Chinese. It doesn’t work because the keyboard doesn’t have the necessary real estate. And the question became: I have a few dozen keys but 100,000 characters. How do I map one onto the other?

Simply put, half of the population on Earth uses the QWERTY keyboard in ways the QWERTY keyboard was never intended to be used, creating a radically different way of interacting with computers.

The root of all of these problems is that computers were designed with English as the default language. So the way English works is just the way computers work today.

M: Every writing system on the planet throughout history is modular, meaning it’s built out of smaller pieces. But computing carefully, brilliantly, and understandably worked on one very specific kind of modularity: modularity as it functions in English.

And then everybody else had to fit themselves into that modularity. Arabic letters connect, so you have to fix [the computer for it]; In South Asian scripts, the combination of a consonant and a vowel changes the shape of the letter overall—that’s not how modularity works in English.

The English modularity is so fundamental in computing that non-Latin speakers are still grappling with the impacts today despite decades of hard work to change things.

Mullaney shared a complaint that Arabic speakers made in 2022 about Adobe InDesign, the most popular publishing design software. As recently as two years ago, pasting a string of Arabic text into the software could cause the text to become messed up, misplacing its diacritic marks, which are crucial for indicating phonetic features of the text. It turns out you need to install a Middle East version of the software and apply some deliberate workarounds to avoid the problem.

M: Latin alphabetic dominance is still alive and well; it has not been overthrown. And there’s a troubling question as to whether it can ever be overthrown. Some turn was made, some path taken that advantaged certain writing systems at a deep structural level and disadvantaged others.

That deeply rooted English-centric design is why mainstream input methods never deviate too far from the keyboards that we all know and love/hate. In the English-speaking world, there have been numerous attempts to reimagine the way text input works. Technologies such as the T9 phone keyboard or the Palm Pilot handwriting alphabet briefly achieved some adoption. But they never stick for long because most developers snap back to QWERTY keyboards at the first opportunity.

M: T9 was born in the context of disability technology and was incorporated into the first mobile phones because button real estate was a major problem (prior to the BlackBerry reintroducing the QWERTY keyboard). It was a necessity; [developers] actually needed to think in a different way. But give me enough space, give me 12 inches by 14 inches, and I’ll default to a QWERTY keyboard.

Every 10 years or so, some Western tech company or inventor announces: “Everybody! I have finally figured out a more advanced way of inputting English at much higher speeds than the QWERTY keyboard.” And time and time again there is zero market appetite.

Will the QWERTY keyboard stick around forever? After this conversation, I’m secretly hoping it won’t. Maybe it’s time for a change. With new technologies like VR headsets, and other gadgets on the horizon, there may come a time when QWERTY keyboards are not the first preference, and non-Latin languages may finally have a chance in shaping the new norm of human-computer interactions.

M: It’s funny, because now as you go into augmented and virtual reality, Silicon Valley companies are like, “How do we overcome the interface problem?” Because you can shrink everything except the QWERTY keyboard. And what Western engineers fail to understand is that it’s not a tech problem—it’s a technological cultural problem. And they just don’t get it. They think that if they just invent the tech, it is going to take off. And thus far, it never has.

If I were a software or hardware developer, I would be hanging out in online role-playing games, just in the chat feature; I would be watching people use their TV remote controls to find the title of the film they’re looking for; I would look at how Roblox players chat with each other. It’s going to come from some arena outside the mainstream, because the mainstream is dominated by QWERTY.

What are other signs of the dominance of English in modern computing? I’d love to hear about the geeky details you’ve noticed. Send them to zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. Today marks the 35th anniversary of the student protests and subsequent massacre in Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

2. A Chinese company that makes laser sensors was labeled by the US government as a security concern. A few months later, it discreetly rebranded as a Michigan-registered company called “American Lidar.” (Wall Street Journal $)

3. It’s a tough time to be a celebrity in China. An influencer dubbed “China’s Kim Kardashian” for his extravagant displays of wealth has just been banned by multiple social media platforms after the internet regulator announced an effort to clear out “ostentatious personas.” (Financial Times $)

4. Cases of Chinese students being rejected entry into the US reveals divisions within the Biden administration. Customs agents, who work for the Department of Homeland Security, have canceled an increasing number of student visas that had already been approved by the State Department. (Bloomberg $)

5. Palau, a small Pacific island nation that’s one of the few countries in the world that recognizes Taiwan as a sovereign country, says it is under cyberattack by China. (New York Times $)

6. After being the first space mission to collect samples from the moon’s far side, China’s Chang’e-6 lunar probe has begun its journey back to Earth. (BBC)

7. The Chinese government just set up the third and largest phase of its semiconductor investment fund to prop up its domestic chip industry. This one’s worth $47.5 billion. (Bloomberg $)

The Chinese generative AI community has been stirred up by the first discovery of a Western large language model plagiarizing a Chinese one, according to the Chinese publication PingWest.

Last week, two undergraduate computer science students at Stanford University released an open-source model called Llama 3-V that they claimed is more powerful than LLMs made by OpenAI and Google, while costing less. But Chinese AI researchers soon found out that Llama 3-V had copied the structure, configuration files, and code from MiniCPM-Llama3-V 2.5, another open-source LLM developed by China’s Tsinghua University and ModelBest Inc, a Chinese startup.

What proved the plagiarism was the fact that the Chinese team secretly trained the model on a collection of Chinese writings on bamboo slips from 2000 years ago, and no other LLMs can recognize the Chinese characters in this ancient writing style accurately. But Llama 3-V could recognize these characters as well as MiniCPM, while making the exact same mistakes as the Chinese model. The students who released Llama 3-V have removed the model and apologized to the Chinese team, but the incident is seen as proof of the rapidly improving capabilities of homegrown LLMs by the Chinese AI community.

Hand-crafted squishy toys (or pressure balls) in the shape of cute animals or desserts have become the latest viral products on Chinese social media. Made in small quantities and sold in limited batches, some of them go for up to $200 per toy on secondhand marketplaces. I mean, they are cute for sure, but I’m afraid the idea of spending $200 on a pressure ball only increases my anxiety.

Enlarge / A sea-borne variant of the commercial Ceres 1 rocket lifts off near the coast of Rizhao, a city of 3 million in China's Shandong province. (credit: VCG via Getty Images)

Welcome to Edition 6.46 of the Rocket Report! It looks like we will be covering the crew test flight of Boeing's Starliner spacecraft and the fourth test flight of SpaceX's giant Starship rocket over the next week. All of this is happening as SpaceX keeps up its cadence of flying multiple Starlink missions per week. The real stars are the Ars copy editors helping make sure our stories don't use the wrong names.

As always, we welcome reader submissions, and if you don't want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Another North Korean launch failure. North Korea's latest attempt to launch a rocket with a military reconnaissance satellite ended in failure due to the midair explosion of the rocket during the first-stage flight this week, South Korea's Yonhap News Agency reports. Video captured by the Japanese news organization NHK appears to show the North Korean rocket disappearing in a fireball shortly after liftoff Monday night from a launch pad on the country's northwest coast. North Korean officials acknowledged the launch failure and said the rocket was carrying a small reconnaissance satellite named Malligyong-1-1.

Enlarge / A Falcon 9 rocket launches the NROL-146 mission from California this week. (credit: SpaceX)

Welcome to Edition 6.45 of the Rocket Report! The most interesting news in launch this week, to me, is that Firefly is potentially up for sale. That makes two of the handful of US companies with operational rockets, Firefly and United Launch Alliance, actively on offer. I'll be fascinated to see what the valuations of each end up being if/when sales go through.

As always, we welcome reader submissions, and if you don't want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Firefly may be up for sale. Firefly Aerospace investors are considering a sale that could value the closely held rocket and Moon lander maker at about $1.5 billion, Bloomberg reports. The rocket company's primary owner, AE Industrial Partners, is working with an adviser on "strategic options" for Firefly. Neither AE nor Firefly commented to Bloomberg about the potential sale. AE invested $75 million into Texas-based Firefly as part of a series B financing round in 2022. The firm made a subsequent investment in its Series C round in November 2023.

Attackers are getting more sophisticated, better armed, and faster. Nothing in Rapid7's 2024 Attack Intelligence Report suggests that this will change.

The post Zero-Day Attacks and Supply Chain Compromises Surge, MFA Remains Underutilized: Rapid7 Report appeared first on SecurityWeek.

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

Last week’s release of GPT-4o, a new AI “omnimodel” that you can interact with using voice, text, or video, was supposed to be a big moment for OpenAI. But just days later, it feels as if the company is in big trouble. From the resignation of most of its safety team to Scarlett Johansson’s accusation that it replicated her voice for the model against her consent, it’s now in damage-control mode.

Add to that another thing OpenAI fumbled with GPT-4o: the data it used to train its tokenizer—a tool that helps the model parse and process text more efficiently—is polluted by Chinese spam websites. As a result, the model’s Chinese token library is full of phrases related to pornography and gambling. This could worsen some problems that are common with AI models: hallucinations, poor performance, and misuse.

I wrote about it on Friday after several researchers and AI industry insiders flagged the problem. They took a look at GPT-4o’s public token library, which has been significantly updated with the new model to improve support of non-English languages, and saw that more than 90 of the 100 longest Chinese tokens in the model are from spam websites. These are phrases like “_free Japanese porn video to watch,” “Beijing race car betting,” and “China welfare lottery every day.”

Anyone who reads Chinese could spot the problem with this list of tokens right away. Some such phrases inevitably slip into training data sets because of how popular adult content is online, but for them to account for 90% of the Chinese language used to train the model? That’s alarming.

“It’s an embarrassing thing to see as a Chinese person. Is that just how the quality of the [Chinese] data is? Is it because of insufficient data cleaning or is the language just like that?” says Zhengyang Geng, a PhD student in computer science at Carnegie Mellon University.

It could be tempting to draw a conclusion about a language or a culture from the tokens OpenAI chose for GPT-4o. After all, these are selected as commonly seen and significant phrases from the respective languages. There’s an interesting blog post by a Hong Kong–based researcher named Henry Luo, who queried the longest GPT-4o tokens in various different languages and found that they seem to have different themes. While the tokens in Russian reflect language about the government and public institutions, the tokens in Japanese have a lot of different ways to say “thank you.”

But rather than reflecting the differences between cultures or countries, I think this explains more about what kind of training data is readily available online, and the websites OpenAI crawled to feed into GPT-4o.

After I published the story, Victor Shih, a political science professor at the University of California, San Diego, commented on it on X: “When you try not [to] train on Chinese state media content, this is what you get.”

It’s half a joke, and half a serious point about the two biggest problems in training large language models to speak Chinese: the readily available data online reflects either the “official,” sanctioned way of talking about China or the omnipresent spam content that drowns out real conversations.

In fact, among the few long Chinese tokens in GPT-4o that aren’t either pornography or gambling nonsense, two are “socialism with Chinese characteristics” and “People’s Republic of China.” The presence of these phrases suggests that a significant part of the training data actually is from Chinese state media writings, where formal, long expressions are extremely common.

OpenAI has historically been very tight-lipped about the data it uses to train its models, and it probably will never tell us how much of its Chinese training database is state media and how much is spam. (OpenAI didn’t respond to MIT Technology Review’s detailed questions sent on Friday.)

But it is not the only company struggling with this problem. People inside China who work in its AI industry agree there’s a lack of quality Chinese text data sets for training LLMs. One reason is that the Chinese internet used to be, and largely remains, divided up by big companies like Tencent and ByteDance. They own most of the social platforms and aren’t going to share their data with competitors or third parties to train LLMs.

In fact, this is also why search engines, including Google, kinda suck when it comes to searching in Chinese. Since WeChat content can only be searched on WeChat, and content on Douyin (the Chinese TikTok) can only be searched on Douyin, this data is not accessible to a third-party search engine, let alone an LLM. But these are the platforms where actual human conversations are happening, instead of some spam website that keeps trying to draw you into online gambling.

The lack of quality training data is a much bigger problem than the failure to filter out the porn and general nonsense in GPT-4o’s token-training data. If there isn’t an existing data set, AI companies have to put in significant work to identify, source, and curate their own data sets and filter out inappropriate or biased content.

It doesn’t seem OpenAI did that, which in fairness makes some sense, given that people in China can’t use its AI models anyway.

Still, there are many people living outside China who want to use AI services in Chinese. And they deserve a product that works properly as much as speakers of any other language do.

How can we solve the problem of the lack of good Chinese LLM training data? Tell me your idea at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. China launched an anti-dumping investigation into imports of polyoxymethylene copolymer—a widely used plastic in electronics and cars—from the US, the EU, Taiwan, and Japan. It’s widely seen as a response to the new US tariff announced on Chinese EVs. (BBC)

2. China’s solar-industry boom is incentivizing farmers to install solar panels and make some extra cash by selling the electricity they generate. (Associated Press)

3. Hedging against the potential devaluation of the RMB, Chinese buyers are pushing the price of gold to all-time highs. (Financial Times $)

4. The Shanghai government set up a pilot project that allows data to be transferred out of China without going through the much-dreaded security assessments, a move that has been sought by companies like Tesla. (Reuters $)

5. China’s central bank fined seven businesses—including a KFC and branches of state-owned corporations—for rejecting cash payments. The popularization of mobile payment has been a good thing, but the dwindling support for cash is also making life harder for people like the elderly and foreign tourists. (Business Insider $)

6. Alibaba and Baidu are waging an LLM price war in China to attract more users. (Bloomberg $)

7. The Chinese government has sanctioned Mike Gallagher, a former Republican congressman who chaired the Select Committee on China and remains a fierce critic of Beijing. (NBC News)

China’s National Health Commission is exploring the relaxation of stringent rules around human genetic data to boost the biotech industry, according to the Chinese publication Caixin. A regulation enacted in 1998 required any research that involves the use of this data to clear an approval process. And there’s even more scrutiny if the research involves foreign institutions.

In the early years of human genetic research, the regulation helped prevent the nonconsensual collection of DNA. But as the use of genetic data becomes increasingly important in discovering new treatments, the industry has been complaining about the bureaucracy, which can add an extra two to four months to research projects. Now the government is holding discussions on how to revise the regulation, potentially lifting the approval process for smaller-scale research and more foreign entities, as part of a bid to accelerate the growth of biotech research in China.

Did you know that the Beijing Capital International Airport has been employing birds of prey to chase away other birds since 2019? This month, the second generation of Beijing’s birdy employees started their work driving away the migratory birds that could endanger aircraft. The airport even has different kinds of raptors—Eurasian hobbies, Eurasian goshawks, and Eurasian sparrowhawks—to deal with the different bird species that migrate to Beijing at different times.

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

We finally know the result of a legal case I’ve been tracking in Hong Kong for almost a year. Last week, the Hong Kong Court of Appeal granted an injunction that permits the city government to go to Western platforms like YouTube and Spotify and demand they remove the protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong,” because the government claims it has been used for sedition.

To read more about how this injunction is specifically designed for Western Big Tech platforms, and the impact it’s likely to have on internet freedom, you can read my story here.

Aside from the depressing implications for pro-democracy movements’ decline in Hong Kong, this lawsuit has also been an interesting case study of the local government’s complicated relationship with internet control and censorship.

I was following this case because it’s a perfect example of how censorship can be built brick by brick. Having reported on China for so long, I sometimes take for granted how powerful and all-encompassing its censorship regime is and need to be reminded that the same can’t be said for most other places in the world.

Hong Kong had a free internet in the past. And unlike mainland China, it remains relatively open: almost all Western platforms and services are still available there, and only a few websites have been censored in recent years.

Since Hong Kong was returned to China from the UK in 1997, the Chinese central government has clashed several times with local pro-democracy movements asking for universal elections and less influence from Beijing. As a result, it started cementing tighter and tighter control over Hong Kong, and people have been worrying about whether its Great Firewall will eventually extend there. But actually, neither Beijing nor Hong Kong may want to see that happen. All the recent legal maneuverings are only necessary because the government doesn’t want a full-on ban of Western platforms.

When I visited Hong Kong last November, it was pretty clear that both Beijing and Hong Kong want to take advantage of the free flow of finance and business through the city. That’s why the Hong Kong government was given tacit permission in 2023 to explore government cryptocurrency projects, even though crypto trading and mining are illegal in China. Hong Kong officials have boasted on many occasions about the city’s value proposition: connecting untapped demand in the mainland to the wider crypto world by attracting mainland investors and crypto companies to set up shop in Hong Kong.

But that wouldn’t be possible if Hong Kong closed off its internet. Imagine a “global” crypto industry that couldn’t access Twitter or Discord. Crypto is only one example, but the things that have made Hong Kong successful—the nonstop exchange of cargo, capital, ideas, and people—would cease to function if basic and universal tools like Google or Facebook became unavailable.

That’s why there are these calculated offenses on internet freedom in Hong Kong. It’s about seeking control but also leaving some breathing space; it’s as much about looking tough on the outside as negotiating with platforms down below; it’s about showing its determination to Beijing but also not showing too much aggression to the West.

For example, the experts I’ve talked to don’t expect the government to request that YouTube remove the videos for everyone globally. More likely, they may ask for the content to be geo-blocked just for users in Hong Kong.

“As long as Hong Kong is still useful as a financial hub, I don’t think they would establish the Great Firewall [there],” says Chung Ching Kwong, a senior analyst at the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, an advocacy organization that connects legislators from over 30 countries working on relations with China.

It’s also the reason why the Hong Kong government has recently come out to say that it won’t outright ban platforms like Telegram and Signal, even though it said that it had received comments from the public asking it to do so.

But coming back to the court decision to restrict “Glory to Hong Kong,” even if the government doesn’t end up enforcing a full-blown ban of the song, as opposed to the more targeted injunction it’s imposed now, it may still result in significant harm to internet freedom.

We are still watching the responses roll in after the court decision last Wednesday. The Hong Kong government is anxiously waiting to hear how Google will react. Meanwhile, some videos have already been taken down, though it’s unclear whether they were pulled by the creators or by the platform.

Michael Mo, a former district councilor in Hong Kong who’s now a postgraduate researcher at the University of Leeds in the UK, created a website right after the injunction was first initiated last June to embed all but one of the YouTube videos the government sought to ban.

The domain name, “gloryto.hk,” was the first test of whether the Hong Kong domain registry would have trouble with it, but nothing has happened to it so far. The second test was seeing how soon the videos would be taken down on YouTube, which is now easy to tell by how many “video unavailable” gaps there are on the page. “Those videos were pretty much intact until the Court of Appeal overturned the rulings of the High Court. The first two have gone,” Mo says.

The court case is having a chilling effect. Even entities that are not governed by the Hong Kong court are taking precautions. Some YouTube accounts owned by media based in Taiwan and the US proactively enabled geo-blocking to restrict people in Hong Kong from watching clips of the song they uploaded as soon as the injunction application was filed, Mo says.

Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future of internet freedom in Hong Kong? Let me know what you think at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. The Biden administration plans to raise tariffs on Chinese-made EVs, from 25% to 100%. Since few Chinese cars are currently sold in the US, this is mostly a move to deter future imports of Chinese EVs. But it could slow down the decarbonization timeline in the US. (ABC News)

2. Government officials from the US and China met in Geneva today to discuss how to mitigate the risks of AI. It’s a notable event, given how rare it is for the two sides to find common ground in the highly politicized field of technology. (Reuters $)

3. It will be more expensive soon to ride the bullet trains in China. A 20% to 39% fare increase is causing controversy among Chinese people. (New York Times $)

4. From executive leadership to workplace culture, TikTok has more in common with its Chinese sister app Douyin than the company wants to admit. (Rest of World)

5. China’s most indebted local governments have started claiming troves of data as “intangible assets” on their accounting books. Given the insatiable appetite for AI training data, they may have a point. (South China Morning Post $)

6. A crypto company with Chinese roots purchased a piece of land in Wyoming for crypto mining. Now the Biden administration is blocking the deal for national security reasons. (Associated Press)

Recently, following an order made by the government, hotels in many major Chinese cities stopped asking guests to submit to facial recognition during check-in.

According to the Chinese publication TechSina, this has had a devastating impact on the industry of facial recognition hardware.

As hotels around the country retire their facial recognition kiosks en masse, equipment made by major tech companies has flooded online secondhand markets at steep discounts. What was sold for thousands of dollars is now resold for as little as 1% of the original price. Alipay, the Alibaba-affiliated payment app, once invested hundreds of millions of dollars to research and roll out these kiosks. Now it’s one of the companies being hit the hardest by the policy change.

I had to double-check that this is not a joke. It turns out that for the past 10 years, the Louvre museum has been giving visitors a Nintendo 3DS—a popular handheld gaming console—as an audio and visual guide.

It feels weird seeing people holding a 3DS up to the Mona Lisa as if they were in their own private Pokémon Go–style gaming world rather than just enjoying the museum. But apparently it doesn’t work very well anyway. Oops.

and it was THE WORST at navigating bc a 3ds can’t tell which direction you’re facing + the floorplan isn’t updated to match ongoing renovations. kept tryna send me into a wall

— taylor (@taylorhansss) May 12, 2024i almost chucked the thing i stg

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

If you could talk again to someone you love who has passed away, would you? For a long time, this has been a hypothetical question. No longer.

Deepfake technologies have evolved to the point where it’s now easy and affordable to clone people’s looks and voices with AI. Meanwhile, large language models mean it’s more feasible than ever before to conduct full conversations with AI chatbots.

I just published a story today about the burgeoning market in China for applying these advances to re-create deceased family members. Thousands of grieving individuals have started turning to dead relatives’ digital avatars for conversations and comfort.

It’s a modern twist on a cultural tradition of talking to the dead, whether at their tombs, during funeral rituals, or in front of their memorial portraits. Chinese people have always liked to tell lost loved ones what has happened since they passed away. But what if the dead could talk back? This is the proposition of at least half a dozen Chinese companies offering “AI resurrection” services. The products, costing a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, are lifelike avatars, accessed in an app or on a tablet, that let people interact with the dead as if they were still alive.

I talked to two Chinese companies that, combined, have provided this service for over 2,000 clients. They describe a growing market of people accepting the technology. Their customers usually look to the products to help them process their grief.

To read more about how these products work and the potential implications of the technology, go here.

However, what I didn’t get into in the story is that the same technology used to clone the dead has also been used in other interesting ways.

For one, this process is being applied not just to private individuals, but also to public figures. Sima Huapeng, CEO and cofounder of the Chinese company Silicon Intelligence, tells me that about one-third of the “AI resurrection” cases he has worked on involve making avatars of dead Chinese writers, thinkers, celebrities, and religious leaders. The generated product is not intended for personal mourning but more for public education or memorial purposes.

Last year, Silicon Intelligence replicated Mei Lanfang, a renowned Peking opera singer born in 1894. The avatar of Mei was commissioned to address a 2023 Peking opera festival held in his hometown, Taizhou. Mei talked about seeing how drastically Taizhou had changed through modern urban development, even though the real artist died in 1961.

But an even more interesting use of this technology is that people are using it to clone themselves while they are still alive, to preserve their memories and leave a legacy.

Sima said this is becoming more popular among successful families that feel the need to pass on their stories. He showed me a video of an avatar the company created for a 92-year-old Chinese entrepreneur, which was displayed on a big vertical monitor screen. The entrepreneur wrote a book documenting his life, and the company only had to feed the whole book to a large language model for it to start role-playing him. “This grandpa cloned himself so he could pass on the stories of his life to the whole family. Even when he dies, he can still talk to his descendants like this,” says Sima.

Sun Kai, another cofounder of Silicon Intelligence, is also featured in my story because he made a replica of his mom, who passed away in 2019. One of his regrets is that he didn’t have enough video recordings of his mom that he could use to train her avatar to be more like her. That inspired him to start recording voice memos of his life and working on his own digital “twin,” even though, in his 40s, death still seems far away.

He compares the process to a complicated version of a photo shoot, but a digital avatar that has his looks, voice, and knowledge can preserve much more information than photographs do.

And there’s still another use: Just as parents can spend money on an expensive photo shoot to capture their children at a specific age, they can also choose to create an AI avatar for the same purpose. “The parents tell us no matter how many photos or videos they took of their 12-year-old kid, it always felt like something was lacking. But once we digitized this kid, they could talk to the 12-year-old version of them anytime, anywhere,” Sun says.

At the end of the day, the deepfake technologies used to clone both the living and the deceased are the same. And seeing that there’s already a market in China for such services, I’m sure these companies will keep on developing more use cases for it.

But what’s also certain is that we’d have to answer a lot more questions about the ethical challenges of these applications, from the issue of consent to violations of copyright.

Would you make a replica of yourself if given the chance? Tell me your thoughts at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. Zhang Yongzhen, the first Chinese scientist to publish a sequence of the covid-19 virus, staged a protest last week over being locked out of his lab—likely a result of the Chinese government’s efforts to discourage research on covid origins. (Associated Press $)

2. Chinese president Xi Jinping is visiting Europe for five days. Half of the trip will be spent in Hungary and Serbia, the only two European countries that are welcoming Chinese investment and manufacturing. Xi is expected to announce an electric-vehicle manufacturing deal in Hungary while he’s there. (Associated Press)

3. China launched a new moon-exploring rover on Friday. It will collect samples near the moon’s south pole, an area where the US and China are competing to build permanent bases. Maybe the Netflix comedy series Space Force will look like a documentary soon. (Wall Street Journal $)

4. Huawei is secretly funding an optics research competition in the US. The act likely isn’t illegal, but it’s deceptive, since university participants, some of whom had vowed to not work with the company, didn’t know the source of the funding. (Bloomberg $)

5. China is quickly catching up on brain-computer interfaces, and there’s strong interest in using the technology for non-medical cognitive improvement. (Wired $)

6. Taiwan has been rocked by frequent earthquakes this year, and developers are racing to make earthquake warning apps that might save lives. One such app has seen user numbers increase from 3,000 to 370,000. (Reuters $)

7. Prestigious Chinese media publications, which still publish hard-hitting stories at times, are being forced to distance themselves from the highest-profile journalism award in Asia to avoid being accused by the government of “colluding with foreign forces.” (Nikkei Asia $)

While generative AI companies have taken the spotlight during the current AI frenzy, China’s older “AI Four Dragons”—four companies that rose to market prominence because of their technological lead in computer vision and facial recognition—are grappling with profit setbacks and commercialization hurdles, reports the Chinese publication Guiji Yanjiushi.

In response to these challenges, the “Dragons” have chosen different strategies. Yitu leaned further into security cameras; Megvii focused on applying computer vision in logistics and the Internet of Things; CloudWalk prioritized AI assistants; and SenseTime, the largest of them all, ventured into generative AI with its self-developed LLMs. Even though they are not as trendy as the startups, some experts believe these established players, having accumulated more computing power and AI talent over the years, may prove to be more resilient in the end.

During this year’s Met Gala, fans were struggling to discern real photos of celebrities from AI-generated ones. To add to the confusion, some social media accounts were running real photos in AI-powered enhancement apps, which slightly distorted the images and made it even harder to tell the difference.

One of the most widely used such apps is called Remini, but few people know that it was actually developed by a Chinese company called Caldron and later acquired by an Italian software company. Remini now has over 20 million users and is extremely profitable. Still, it seems its AI enhancement tools have a long way to go.

bestie… @2015smetgala it’s time to delete the remini app… you’ve gone too far https://t.co/Q4Aj2454U8 pic.twitter.com/yqH46EJlJd

— swiftie wins(@swifferwins) May 7, 2024

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

Allow me to indulge in a little reflection this week. Last week, the divest-or-ban TikTok bill was passed in Congress and signed into law. Four years ago, when I was just starting to report on the world of Chinese technologies, one of my first stories was about very similar news: President Donald Trump announcing he’d ban TikTok.

That 2020 executive order came to nothing in the end—it was blocked in the courts, put aside after the presidency changed hands, and eventually withdrawn by the Biden administration. Yet the idea—that the US government should ban TikTok in some way—never went away. It would repeatedly be suggested in different forms and shapes. And eventually, on April 24, 2024, things came full circle.

A lot has changed in the four years between these two news cycles. Back then, TikTok was a rising sensation that many people didn’t understand; now, it’s one of the biggest social media platforms, the originator of a generation-defining content medium, and a music-industry juggernaut.

What has also changed is my outlook on the issue. For a long time, I thought TikTok would find a way out of the political tensions, but I’m increasingly pessimistic about its future. And I have even less hope for other Chinese tech companies trying to go global. If the TikTok saga tells us anything, it’s that their Chinese roots will be scrutinized forever, no matter what they do.

I don’t believe TikTok has become a larger security threat now than it was in 2020. There have always been issues with the app, like potential operational influence by the Chinese government, the black-box algorithms that produce unpredictable results, and the fact that parent company ByteDance never managed to separate the US side and the China side cleanly, despite efforts (one called Project Texas) to store and process American data locally.

But none of those problems got worse over the last four years. And interestingly, while discussions in 2020 still revolved around potential remedies like setting up data centers in the US to store American data or having an organization like Oracle audit operations, those kinds of fixes are not in the law passed this year. As long as it still has Chinese owners, the app is not permissible in the US. The only thing it can do to survive here is transfer ownership to a US entity.

That’s the cold, hard truth not only for TikTok but for other Chinese companies too. In today’s political climate, any association with China and the Chinese government is seen as unacceptable. It’s a far cry from the 2010s, when Chinese companies could dream about developing a killer app and finding audiences and investors around the globe—something many did pull off.

There’s something I wrote four years ago that still rings true today: TikTok is the bellwether for Chinese companies trying to go global.

The majority of Chinese tech giants, like Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu, operate primarily within China’s borders. TikTok was the first to gain mass popularity in lots of other countries across the world and become part of daily life for people outside China. To many Chinese startups, it showed that the hard work of trying to learn about foreign countries and users can eventually pay off, and it’s worth the time and investment to try.

On the other hand, if even TikTok can’t get itself out of trouble, with all the resources that ByteDance has, is there any hope for the smaller players?

When TikTok found itself in trouble, the initial reaction of these other Chinese companies was to conceal their roots, hoping they could avoid attention. During my reporting, I’ve encountered multiple companies that fret about being described as Chinese. “We are headquartered in Boston,” one would say, while everyone in China openly talked about its product as the overseas version of a Chinese app.

But with all the political back-and-forth about TikTok, I think these companies are also realizing that concealing their Chinese associations doesn’t work—and it may make them look even worse if it leaves users and regulators feeling deceived.

With the new divest-or-ban bill, I think these companies are getting a clear signal that it’s not the technical details that matter—only their national origin. The same worry is spreading to many other industries, as I wrote in this newsletter last week. Even in the climate and renewable power industries, the presence of Chinese companies is becoming increasingly politicized. They, too, are finding themselves scrutinized more for their Chinese roots than for the actual products they offer.

Obviously, none of this is good news to me. When they feel unwelcome in the US market, Chinese companies don’t feel the need to talk to international media anymore. Without these vital conversations, it’s even harder for people in other countries to figure out what’s going on with tech in China.

Instead of banning TikTok because it’s Chinese, maybe we should go back to focus on what TikTok did wrong: why certain sensitive political topics seem deprioritized on the platform; why Project Texas has stalled; how to make the algorithmic workings of the platform more transparent. These issues, instead of whether TikTok is still controlled by China, are the things that actually matter. It’s a harder path to take than just banning the app entirely, but I think it’s the right one.

Do you believe the TikTok ban will go through? Let me know your thoughts at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. Facing the possibility of a total ban on TikTok, influencers and creators are making contingency plans. (Wired $)

2. TSMC has brought hundreds of Taiwanese employees to Arizona to build its new chip factory. But the company is struggling to bridge cultural and professional differences between American and Taiwanese workers. (Rest of World)

3. The US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, met with Chinese president Xi Jinping during a visit to China this week. (New York Times $)

4. Half of Russian companies’ payments to China are made through middlemen in Hong Kong, Central Asia, or the Middle East to evade sanctions. (Reuters $)

5. A massive auto show is taking place in Beijing this week, with domestic electric vehicles unsurprisingly taking center stage. (Associated Press)

6. Beijing has hosted two rival Palestinian political groups, Hamas and Fatah, to talk about potential reconciliation. (Al Jazeera)

The Chinese dubbing community is grappling with the impacts of new audio-generating AI tools. According to the Chinese publication ACGx, for a new audio drama, a music company licensed the voice of the famous dubbing actor Zhao Qianjing and used AI to transform it into multiple characters and voice the entire script.

But online, this wasn’t really celebrated as an advancement for the industry. Beyond criticizing the quality of the audio drama (saying it still doesn’t sound like real humans), dubbers are worried about the replacement of human actors and increasingly limited opportunities for newcomers. Other than this new audio drama, there have been several examples in China where AI audio generation has been used to replace human dubbers in documentaries and games. E-book platforms have also allowed users to choose different audio-generated voices to read out the text.

While in Beijing, Antony Blinken visited a record store and bought two vinyl records—one by Taylor Swift and another by the Chinese rock star Dou Wei. Many Chinese (and American!) people learned for the first time that Blinken had previously been in a rock band.

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

I’ve wanted to learn more about the world of solar panels ever since I realized just how dominant Chinese companies have become in this field. Although much of the technology involved was invented in the US, today about 80% of the world’s solar manufacturing takes place in China. For some parts of the process, it’s responsible for even more: 97% of wafer manufacturing, for example.

So I jumped at the opportunity to interview Shawn Qu, the founder and chairman of Canadian Solar, one of the largest and longest-standing solar manufacturing companies in the world, last week.

Qu’s company provides a useful lens on wider efforts by the US to reshape the global solar supply chain and bring more of it back to American shores. Although most of its production is still in China and Southeast Asia, it’s now building two factories in the US, spurred on by incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act. You can read my story here.

I met Qu in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he was attending the Harvard College China Forum, a two-day annual conference that often draws a fair number of Chinese entrepreneurs. I also attended, hoping to meet representatives of Chinese tech companies there.

At the conference, I noticed three interesting things.

One, there was a glaring absence of Chinese consumer tech companies. With the exception of one US-based manager from TikTok, I didn’t see anyone from Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, or ByteDance.

These companies, with their large influence on Chinese people’s everyday lives, used to be the stars of discussions around China’s tech sector. If you had come to the Harvard conference before covid-19, you would have met plenty of people representing them, as well as the venture capitalists that funded their successes. You can get a sense just by reading past speaker lists: executives from Xiaomi, Ant Financial, Sogou, Sequoia China, and Hillhouse Capital. These are the equivalents of Mark Zuckerberg and Peter Thiel in China’s tech world.

But these companies have become much more low profile since then, for a couple of main reasons. First, they underwent a harsh domestic crackdown after the government decided to tame them. (I recently talked to Angela Zhang, a law professor studying Chinese tech regulations, to understand these crackdowns.) And second, they have become the subject of national security scrutiny in the US, making it politically unwise for them to engage too much on the public stage here.

The second thing I noticed at the conference is what stood in their place: a batch of new Chinese companies, mostly in climate tech. William Li, the CEO of China’s EV startup NIO, was one of the most popular guest speakers during the conference’s opening ceremony this year. There were at least three solar panel companies present—two (JA Solar and Canadian Solar) among the top-tier manufacturers in the world, and a third that sells solar panels to Latin America. There were also many academics, investors, and even influencers working in the field of electric vehicles and other electrified transportation methods.

It’s clear that amid the increasingly urgent task of addressing climate change, China’s climate technology companies have become the new stars of the show. And they are very much willing to appear on the global stage, both bragging about their technological lead and seeking new markets.

“The Chinese entrepreneurs are very eager,” says Jinhua Zhao, a professor studying urban transportation at MIT, who also spoke on one of the panels at the conference. “They want to come out. I think the Chinese government side also started to send signals, inviting foreign leadership and financial industries to visit China. I see a lot of gestures.”

The problem, however, is they are also becoming subject to a lot of political animosity in the US. The Biden administration has started an investigation into Chinese-made cars, mostly electric vehicles; Chinese battery companies have been navigating a minefield of politicians’ resistance to their setting up plants in North America; and Chinese solar panel companies have been subject to sky-high tariffs.

Back in the mid-2010s, when Chinese consumer tech companies emerged onto the global stage, the US and China had a warm relationship, creating a welcoming environment. Unfortunately, that’s not something climate tech companies can enjoy today. Even though climate change is a global issue that requires countries to collaborate, political tensions stand in the way when companies and investors on opposite sides try to work together.

On that note, the last thing I noticed at the conference is a rising geopolitical force in tech: the Middle East. A few speakers at the conference are working in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and they represent other deep-pocketed players who are betting on technologies like EVs and AI in both the United States and China.

But can they navigate the tensions and benefit from the technological advantages on both sides? It’ll be interesting to watch how that unfolds.

What do you think of the role of the Middle East in the future of climate technologies? Let me know your thoughts at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. A batch of documents mistakenly unsealed by a Pennsylvania court reveals the origin story of TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance. Who knew it started out as a real estate venture? (New York Times $)

2. Vladimir Potanin, Russia’s richest man, said he would move some of his copper smelting factories to China to reduce the impact of Western sanctions, which block Russian companies from using international payment systems. (Financial Times $)

3. Chinese universities have found a way to circumvent the US export ban on high-end Nvidia chips: by buying resold server products made by Dell, Super Micro Computer, and Taiwan’s Gigabyte Technology. (Reuters $)

4. TikTok is testing “TikTok Notes,” a rival product to Instagram, in Australia and Canada. (The Verge)

5. Since there’s no route for personal bankruptcy in China, those who are unable to pay their debts are being penalized in novel ways: they can’t take high-speed trains, fly on planes, stay in nice hotels, or buy expensive insurance policies. (Wall Street Journal $)

6. The hunt for the origins of covid-19 has stalled in China, as Chinese politicians worry about being blamed for the findings. (Associated Press)

7. Because of pressure from the US government, Mexico will not hand out tax cuts and other incentives to Chinese EV companies. (Reuters $)

Until last year, it was normal for Chinese hotels to require facial recognition to check guests in, but the city of Shanghai is now turning against the practice, according to the Chinese publication 21st Century Business Herald. The police bureau of Shanghai recently published a notice that says “scanning faces” is required only if guests don’t have any identity documents. Otherwise, they have the right to refuse it. Most hotel chains in Shanghai, and some in other cities, have updated their policies in response.

China has a national facial recognition database tied to the government ID system, and businesses such as hotels can access it to verify customers’ identities. However, Chinese people are increasingly pushing back on the necessity of facial recognition in scenarios like this, and questioning whether hotels are handling such sensitive biometric data properly.

The latest queer icon in Asia is Nymphia Wind, the drag persona of a 28-year-old Taiwanese-American named Leo Tsao, who just won the latest season of RuPaul’s Drag Race. Fully embracing the color yellow as part of her identity, Nymphia Wind is also called the “Banana Buddha” by her fans. She’s hosting shows in Taoist temples in Taiwan, attracting audiences old and young.

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

If you’re a longtime subscriber to this newsletter, you know that I talk about China’s tech policies all the time. To me, it’s always a challenge to understand and explain the government’s decisions to bolster or suppress a certain technology. Why does it favor this sector instead of that one? What triggers officials to suddenly initiate a crackdown? The answers are never easy to come by.

So I was inspired after talking to Angela Huyue Zhang, a law professor in Hong Kong who’s coming to teach at the University of Southern California this fall, about her new book on interpreting the logic and patterns behind China’s tech regulations.

We talked about how the Chinese government almost always swings back and forth between regulating tech too much and not enough, how local governments have gone to great lengths to protect local tech companies, and why AI companies in China are receiving more government goodwill than other sectors today.

To learn more about Zhang’s fascinating interpretation of the tech regulations in China, read my story published today.

In this newsletter, I want to show you a particularly interesting part of the conversation we had, where Zhang expanded on how market overreactions to Chinese tech policies have become an integral part of the tech regulator’s toolbox today.

The capital markets, perpetually betting on whether tech companies are going to fare better or worse, are always looking for policy signals on whether China is going to start a new crackdown on certain technologies. As a result, they often overreact to every move by the Chinese government.

Zhang: “Investors are already very nervous. They see any sort of regulatory signal very negatively, which is what happened last December when a gaming regulator sent out a draft proposal to regulate and curb gaming activities. It just spooked the market. I mean, actually, that draft law is nothing particularly unusual. It’s quite similar to the previous draft circulated among the lawyers, and there are just a couple of provisions that need a little bit of clarity. But investors were just so panicked.”

That specific example saw nearly $80 billion wiped from the market value of China’s two top gaming companies. The drastic reaction actually forced China’s tech regulators to temporarily shelve the draft law to quell market pessimism.

Zhang: If you look at previous crackdowns, the biggest [damage] that these firms receive is not in the form of a monetary fine. It is in the form of the [changing] market sentiment.

What the agency did at that time was deliberately inflict reputational damage on [Alibaba] by making this surprise announcement on its website, even though it was just one sentence saying “We are investigating Alibaba for monopolistic practice.” But they already caused the market to panic. As soon as they made the announcement, it wiped off $100 billion market cap from this firm overnight. Compared with that, the ultimate fine of $2.8 billion [that Alibaba had to pay] is nothing.

China’s tech regulators use the fact that the stock market predictably overreacts to policy signals to discipline unruly tech companies with minimum effort.

Zhang: These agencies are very adept at inflicting reputational damage. That’s why the market sentiment is something that they like to [utilize], and that kind of thing tends to be ignored because people tend to fix any attention on the law.

But playing the market this way is risky. As in the previously mentioned example of the video-game policy, regulators can’t always control how significant the overreactions become, so they risk inflicting broader economic damage that they don’t want to be responsible for.

Zhang: They definitely learned how badly investors can react to their regulatory actions. And if anything, they are very cautious and nervous as well. I think they will be risk-averse in introducing harsh regulations.

I also think the economic downturn has dampened the voices of certain agencies that used to be very aggressive during the crackdown, like the Cyberspace Administration of China. Because it seems like what they did caused tremendous trauma for the Chinese economy.

The fear of causing negative economic fallout by introducing harsh regulatory measures means these government agencies may turn to softer approaches, Zhang says.

Zhang: Now, if they want to take a softer approach, they would have a cup of tea with these firms and say “Here’s what you can do.” So it’s a more consensual approach now than those surprise attacks.

Do you agree that Chinese regulators have learned to take a softer approach to disciplining tech companies? Let me know your thoughts at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. Covert Chinese accounts are pretending to be Trump supporters on social media and stoking domestic divisions ahead of November’s US election, taking a page out of the Russian playbook in 2016. (New York Times $)

2. Tesla canceled long-promised plans to release an inexpensive car. Its Chinese rivals are selling EV alternatives at less than one-third the price of the cheapest Teslas. (Reuters $)

3. Donghua Jinlong, a factory in China that makes a nutritional additive called “high-quality industrial-grade glycine,” has unexpectedly become a meme adored by TikTok users. No one really knows why. (You May Also Like)

4. Joe Tsai, Alibaba’s chairman, said in a recent interview that he believes Chinese AI firms lag behind US peers “by two years.” (South China Morning Post $)

5. At first glance, a hacker behind a multi-year attempt to hack supply chains seemed to come from China. But details about the hacker’s work hours suggest that countries in Eastern Europe or the Middle East could be the real culprit. (Wired $)

6. While visiting China, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said that she would not rule out potential tariffs on China’s green energy exports, including products like solar panels and electric vehicles. (CNBC)

Hong Kong’s food delivery scene used to be split between the German-owned platform Foodpanda and the UK-owned Deliveroo. But the Chinese giant Meituan has been working since May 2023 on cracking into the scene with its new app KeeTa, according to the Chinese publication Zhengu Lab. It has so far managed to capture over 20% of the market.

Both of Meituan’s rivals waive the delivery fee only for larger orders, which makes it hard for people to order food alone. So Meituan decided to position itself as the platform for solo diners by waiving delivery fees for most restaurants, saving users up to 30% in costs. To compete with the established players, the company also pays higher wages to delivery workers and charges lower commission fees to restaurants.

Compared with mainland China, Hong Kong has a tiny delivery market. But Meituan’s efforts here represent a first step as it works to expand into more countries overseas, the company has said.

For some hard-to-explain reasons, every time US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen visits China, Chinese social media becomes obsessed with what and how she eats during the trip. This week, people were zooming into a seven-second video of Yellen’s dinner to scrutinize … her chopstick skills. Whyyyyyyy?

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

Like most reporters, I have accounts on every social media platform you can think of. But for the longest time, I was not on Threads, the rival to X (formerly Twitter) released by Meta last year. The way it has to be tied to your Instagram account didn’t sit well with me, and as its popularity dwindled, I felt maybe it was not necessary to use it.

But I finally joined Threads last week after I discovered that the app has unexpectedly blown up among Taiwanese users. For months, Threads has been the most downloaded app in Taiwan, as users flock to the platform to talk about politics and more. I talked to academics and Taiwanese Threads users about why the Meta-owned platform got a redemption arc in Taiwan this year. You can read what I discovered here.

I first noticed the trend on Instagram, which occasionally shows you a few trending Threads posts to try to entice you to join. After seeing them a few times, I realized there was a pattern: most of these were written by Taiwanese people talking about Taiwan.

That was a rare experience for me, since I come from China and write primarily about China. Social media algorithms have always shown me accounts similar to mine. Although people from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan all write in Chinese, the characters we use and the expressions we choose are quite different, making it easy to spot your own people. And on most platforms that are truly global, the conversations in Chinese are mostly dominated by people in or from mainland China, since its population far outnumbers the rest.

As I dug into the phenomenon, it soon turned out that Threads’ popularity has been surging at an unparalleled pace in Taiwan. Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram, publicly acknowledged that Threads has been doing “exceptionally well in Taiwan, of all places.” Data from Sensor Tower, a market intelligence firm, shows that Threads has been the most downloaded social network app on iPhone and Android in Taiwan almost every single day of 2024. On the platform itself, Taiwanese users are also belatedly realizing their influence when they see that comments under popular accounts, like a K-pop group, come mostly from fellow Taiwanese users.

But why did Threads succeed in Taiwan when it has failed in so many other places? My interviews with users and scholars revealed a few reasons.

First, Taiwanese people never really adopted Twitter. Only 1% to 5% of them regularly use the platform, now called X, estimates Austin Wang, a political science professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. The mainstream population uses Facebook and Instagram, but still yearns for a platform for short text posts. The global launch of Threads basically gave these users a good reason to try out a Twitter-like product.

But more important, Taiwan’s presidential election earlier this year means there was a lot to talk, debate, and commiserate about. Starting in November, many supporters of Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) “gathered to Threads and used it as a mobilization tool,” Wang says. “Even DPP presidential candidate Lai received more interaction on Threads than Instagram and Facebook.”

It turns out that even though Meta has tried to position Threads as a less political version of X, what actually underpinned its success in Taiwan was still the universal desire to talk about politics.

“Taiwanese people gather on Threads because of the freedom to talk about politics [here],” Liu, a designer in Taipei who joined in January because of the elections, tells me. “For Threads to depoliticize would be shooting itself in the foot.”

The fact that there are an exceptionally large number of Taiwanese users on Threads also makes it a better place to talk about internal politics, she says, because it won’t easily be overshadowed or hijacked by people outside Taiwan. The more established platforms like Facebook and X are rife with bots, disinformation campaigns, and controversial content moderation policies. On Threads there’s minimal interference with what the Taiwanese users are saying. That feels like a fresh breeze to Liu.

But I can’t help feeling that Threads’ popularity in Taiwan could easily go awry. Meta’s decision to keep Threads distanced from political content is one factor that could derail Taiwanese users’ experience; an influx of non-Taiwanese users, if the platform actually manages to become more successful and popular in other parts of the world, could also introduce heated disagreements and all the additional reasons why other platforms have deteriorated.

These are some tough questions to answer for Meta, because users will simply flow to the next trendy, experimental platform if Threads doesn’t feel right anymore. Its success in Taiwan so far is a rare win for the company, but preserving that success and replicating it elsewhere will require a lot more work.

Do you believe Threads stands a chance of rivaling X (Twitter) in places other than Taiwan? Let me know your thoughts at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

1. Morris Chang, who founded the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company at the age of 55, is an outlier in today’s tech industry, where startup founders usually start in their 20s. (Wall Street Journal $)

2. A group of Chinese researchers used the technology behind hypersonic missiles to make high-speed trains safer. (South China Morning Post $)

3. The US government is considering cutting the so-called de minimis exemption from import duties, which makes it cheap for Temu and Shein to send packages to the US. But lots of US companies also benefit from the exemption now. (The Information $)

4. The Chinese commerce minister will visit Europe soon to plead his country’s case amid the European Commission’s investigation into Chinese electric vehicles. (Reuters $)

5. After three years of unsuccessful competition with WhatsApp, ByteDance’s messaging app designed for the African market finally shut down last month. (Rest of World)

6. The rapid progress of AI makes it seem less necessary to learn a foreign language. But there are still things AI loses in translation. (The Atlantic $)

7. This is the incredible story of a Chinese man who takes his piano to play outdoors at places of public grief: in front of the covid quarantine barriers in Wuhan, at the epicenter of an earthquake, on a river that submerged villages. And he plays the same song—the only song he knows, composed by the Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto. (NPR)