Cloudflare Zero-Day Let Attackers Bypass WAF via ACME Certificate Validation Path

During a recent investigation, we uncovered a phishing operation that combines free hosting on developer platforms with compromised legitimate websites to build convincing banking and insurance login portals. These fake pages don’t just grab a username and password–they also ask for answers to secret questions and other “backup” data that attackers can use to bypass multi-factor authentication and account recovery protections.

Instead of sending stolen data to a traditional command-and-control server, the kit forwards every submission to a Telegram bot. That gives the attackers a live feed of fresh logins they can use right away. It also sidesteps many domain-based blocking strategies and makes swapping infrastructure very easy.

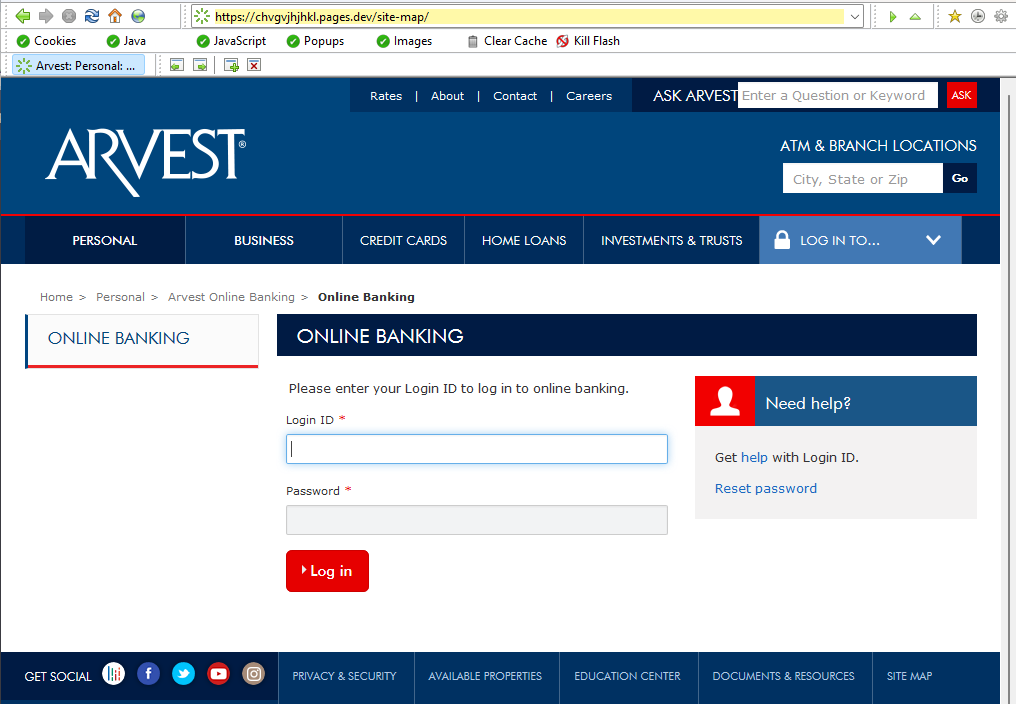

Phishing groups increasingly use services like Cloudflare Pages (*.pages.dev) to host their fake portals, sometimes copying a real login screen almost pixel for pixel. In this case, the actors spun up subdomains impersonating financial and healthcare providers. The first one we found was impersonating Heartland bank Arvest.

To be clear, these companies have not been compromised and accessing their websites from trusted domains remains safe. What is instead happening is that these companies are having their online likenesses faked as a way to fool victims in a longer attack chain that often starts with a phishing email.

On closer look, the phishing site shows visitors two “failed login” screens, prompts for security questions, and then sends all credentials and answers to a Telegram bot.

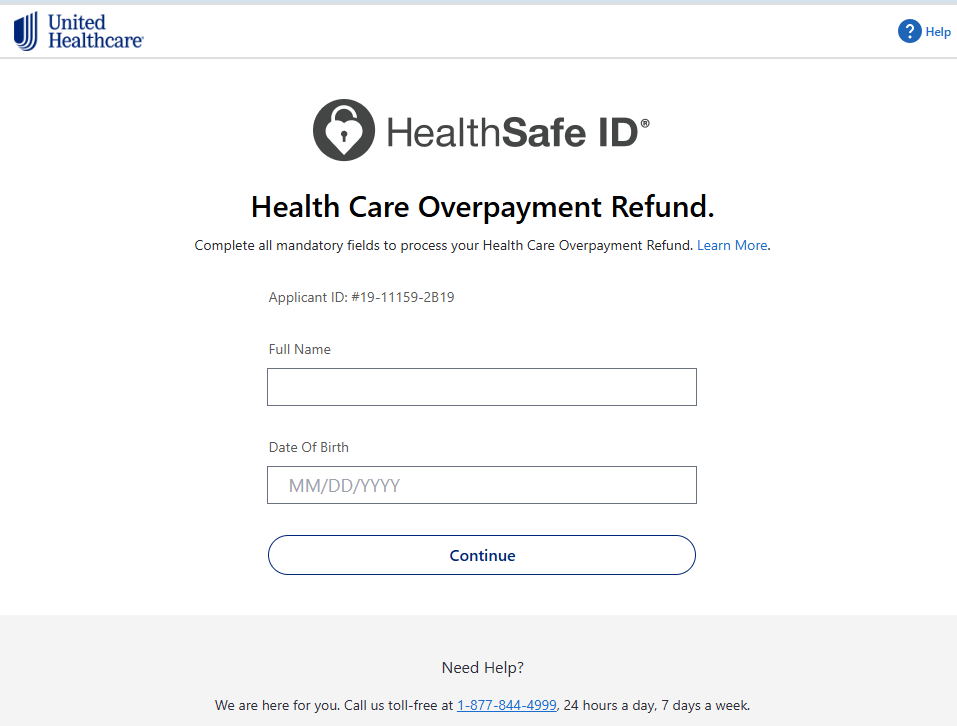

Comparing their infrastructure with other sites, we found one impersonating a much more widely known brand: United Healthcare.

In this case, the phishers abused a compromised website as a redirector. Attackers took over a legitimate-looking domain like biancalentinidesigns[.]com and saddle it with long, obscure paths for phishing or redirection. Emails link to the real domain first, which then forwards the victim to the active Cloudflare pages phishing site. Messages containing a familiar or benign-looking domain are more likely to slip past spam filters than links that go straight to an obviously new cloud-hosted subdomain.

Cloud-based hosting also makes takedowns harder. If one *.pages.dev hostname gets reported and removed, attackers can quickly deploy the same kit under another random subdomain and resume operations.

The phishing kit at the heart of this campaign follows a multi-step pattern designed to look like a normal sign-in flow while extracting as much sensitive data as possible.

Instead of using a regular form submission to a visible backend, JavaScript harvests the fields and bundles them into a message sent straight to the Telegram API.. That message can include the victim’s IP address, user agent, and all captured fields, giving criminals a tidy snapshot they can use to bypass defenses or sign in from a similar environment.

The exfiltration mechanism is one of the most worrying parts. Rather than pushing credentials to a single hosted panel, the kit posts them into one or more Telegram chats using bot tokens and chat IDs hardcoded in the JavaScript. As soon as a victim submits a form, the operator receives a message in their Telegram client with the details, ready for immediate use or resale.

This approach offers several advantages for the attackers: they can change bots and chat IDs frequently, they do not need to maintain their own server, and many security controls pay less attention to traffic that looks like a normal connection to a well-known messaging platform. Cycling multiple bots and chats gives them redundancy if one token is reported and revoked.

Putting all the pieces together, a victim’s experience in this kind of campaign often looks like this:

From the victim’s point of view, nothing seems unusual beyond an odd-looking link and a failed sign-in. For the attackers, the mix of free hosting, compromised redirectors, and Telegram-based exfiltration gives them speed, scale, and resilience.

The bigger trend behind this campaign is clear: by leaning on free web hosting and mainstream messaging platforms, phishing actors avoid many of the choke points defenders used to rely on, like single malicious IPs or obviously shady domains. Spinning up new infrastructure is cheap, fast, and largely invisible to victims.

Education and a healthy dose of skepticism are key components to staying safe. A few habits can help you avoid these portals:

*.pages.dev, *.netlify.app, or on strange paths on unrelated sites.Pro tip: Malwarebytes free Browser Guard extension blocked these websites.

We don’t just report on threats—we help safeguard your entire digital identity

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Protect your, and your family’s, personal information by using identity protection.

An intermittent outage at Cloudflare on Tuesday briefly knocked many of the Internet’s top destinations offline. Some affected Cloudflare customers were able to pivot away from the platform temporarily so that visitors could still access their websites. But security experts say doing so may have also triggered an impromptu network penetration test for organizations that have come to rely on Cloudflare to block many types of abusive and malicious traffic.

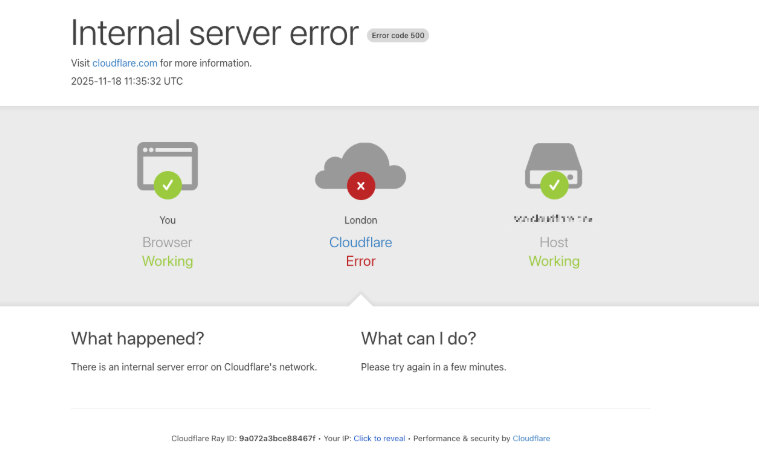

At around 6:30 EST/11:30 UTC on Nov. 18, Cloudflare’s status page acknowledged the company was experiencing “an internal service degradation.” After several hours of Cloudflare services coming back up and failing again, many websites behind Cloudflare found they could not migrate away from using the company’s services because the Cloudflare portal was unreachable and/or because they also were getting their domain name system (DNS) services from Cloudflare.

However, some customers did manage to pivot their domains away from Cloudflare during the outage. And many of those organizations probably need to take a closer look at their web application firewall (WAF) logs during that time, said Aaron Turner, a faculty member at IANS Research.

Turner said Cloudflare’s WAF does a good job filtering out malicious traffic that matches any one of the top ten types of application-layer attacks, including credential stuffing, cross-site scripting, SQL injection, bot attacks and API abuse. But he said this outage might be a good opportunity for Cloudflare customers to better understand how their own app and website defenses may be failing without Cloudflare’s help.

“Your developers could have been lazy in the past for SQL injection because Cloudflare stopped that stuff at the edge,” Turner said. “Maybe you didn’t have the best security QA [quality assurance] for certain things because Cloudflare was the control layer to compensate for that.”

Turner said one company he’s working with saw a huge increase in log volume and they are still trying to figure out what was “legit malicious” versus just noise.

“It looks like there was about an eight hour window when several high-profile sites decided to bypass Cloudflare for the sake of availability,” Turner said. “Many companies have essentially relied on Cloudflare for the OWASP Top Ten [web application vulnerabilities] and a whole range of bot blocking. How much badness could have happened in that window? Any organization that made that decision needs to look closely at any exposed infrastructure to see if they have someone persisting after they’ve switched back to Cloudflare protections.”

Turner said some cybercrime groups likely noticed when an online merchant they normally stalk stopped using Cloudflare’s services during the outage.

“Let’s say you were an attacker, trying to grind your way into a target, but you felt that Cloudflare was in the way in the past,” he said. “Then you see through DNS changes that the target has eliminated Cloudflare from their web stack due to the outage. You’re now going to launch a whole bunch of new attacks because the protective layer is no longer in place.”

Nicole Scott, senior product marketing manager at the McLean, Va. based Replica Cyber, called yesterday’s outage “a free tabletop exercise, whether you meant to run one or not.”

“That few-hour window was a live stress test of how your organization routes around its own control plane and shadow IT blossoms under the sunlamp of time pressure,” Scott said in a post on LinkedIn. “Yes, look at the traffic that hit you while protections were weakened. But also look hard at the behavior inside your org.”

Scott said organizations seeking security insights from the Cloudflare outage should ask themselves:

1. What was turned off or bypassed (WAF, bot protections, geo blocks), and for how long?

2. What emergency DNS or routing changes were made, and who approved them?

3. Did people shift work to personal devices, home Wi-Fi, or unsanctioned Software-as-a-Service providers to get around the outage?

4. Did anyone stand up new services, tunnels, or vendor accounts “just for now”?

5. Is there a plan to unwind those changes, or are they now permanent workarounds?

6. For the next incident, what’s the intentional fallback plan, instead of decentralized improvisation?

In a postmortem published Tuesday evening, Cloudflare said the disruption was not caused, directly or indirectly, by a cyberattack or malicious activity of any kind.

“Instead, it was triggered by a change to one of our database systems’ permissions which caused the database to output multiple entries into a ‘feature file’ used by our Bot Management system,” Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince wrote. “That feature file, in turn, doubled in size. The larger-than-expected feature file was then propagated to all the machines that make up our network.”

Cloudflare estimates that roughly 20 percent of websites use its services, and with much of the modern web relying heavily on a handful of other cloud providers including AWS and Azure, even a brief outage at one of these platforms can create a single point of failure for many organizations.

Martin Greenfield, CEO at the IT consultancy Quod Orbis, said Tuesday’s outage was another reminder that many organizations may be putting too many of their eggs in one basket.

“There are several practical and overdue fixes,” Greenfield advised. “Split your estate. Spread WAF and DDoS protection across multiple zones. Use multi-vendor DNS. Segment applications so a single provider outage doesn’t cascade. And continuously monitor controls to detect single-vendor dependency.”

For the past week, domains associated with the massive Aisuru botnet have repeatedly usurped Amazon, Apple, Google and Microsoft in Cloudflare’s public ranking of the most frequently requested websites. Cloudflare responded by redacting Aisuru domain names from their top websites list. The chief executive at Cloudflare says Aisuru’s overlords are using the botnet to boost their malicious domain rankings, while simultaneously attacking the company’s domain name system (DNS) service.

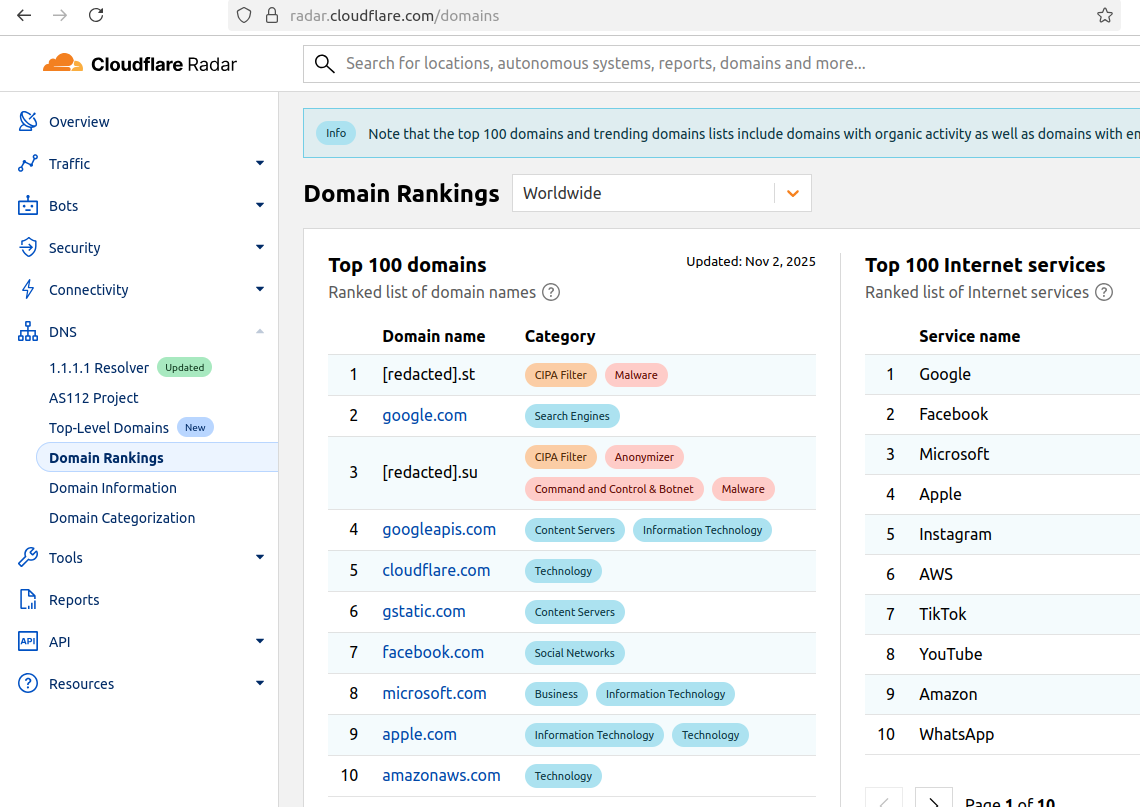

The #1 and #3 positions in this chart are Aisuru botnet controllers with their full domain names redacted. Source: radar.cloudflare.com.

Aisuru is a rapidly growing botnet comprising hundreds of thousands of hacked Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as poorly secured Internet routers and security cameras. The botnet has increased in size and firepower significantly since its debut in 2024, demonstrating the ability to launch record distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks nearing 30 terabits of data per second.

Until recently, Aisuru’s malicious code instructed all infected systems to use DNS servers from Google — specifically, the servers at 8.8.8.8. But in early October, Aisuru switched to invoking Cloudflare’s main DNS server — 1.1.1.1 — and over the past week domains used by Aisuru to control infected systems started populating Cloudflare’s top domain rankings.

As screenshots of Aisuru domains claiming two of the Top 10 positions ping-ponged across social media, many feared this was yet another sign that an already untamable botnet was running completely amok. One Aisuru botnet domain that sat prominently for days at #1 on the list was someone’s street address in Massachusetts followed by “.com”. Other Aisuru domains mimicked those belonging to major cloud providers.

Cloudflare tried to address these security, brand confusion and privacy concerns by partially redacting the malicious domains, and adding a warning at the top of its rankings:

“Note that the top 100 domains and trending domains lists include domains with organic activity as well as domains with emerging malicious behavior.”

Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince told KrebsOnSecurity the company’s domain ranking system is fairly simplistic, and that it merely measures the volume of DNS queries to 1.1.1.1.

“The attacker is just generating a ton of requests, maybe to influence the ranking but also to attack our DNS service,” Prince said, adding that Cloudflare has heard reports of other large public DNS services seeing similar uptick in attacks. “We’re fixing the ranking to make it smarter. And, in the meantime, redacting any sites we classify as malware.”

Renee Burton, vice president of threat intel at the DNS security firm Infoblox, said many people erroneously assumed that the skewed Cloudflare domain rankings meant there were more bot-infected devices than there were regular devices querying sites like Google and Apple and Microsoft.

“Cloudflare’s documentation is clear — they know that when it comes to ranking domains you have to make choices on how to normalize things,” Burton wrote on LinkedIn. “There are many aspects that are simply out of your control. Why is it hard? Because reasons. TTL values, caching, prefetching, architecture, load balancing. Things that have shared control between the domain owner and everything in between.”

Alex Greenland is CEO of the anti-phishing and security firm Epi. Greenland said he understands the technical reason why Aisuru botnet domains are showing up in Cloudflare’s rankings (those rankings are based on DNS query volume, not actual web visits). But he said they’re still not meant to be there.

“It’s a failure on Cloudflare’s part, and reveals a compromise of the trust and integrity of their rankings,” he said.

Greenland said Cloudflare planned for its Domain Rankings to list the most popular domains as used by human users, and it was never meant to be a raw calculation of query frequency or traffic volume going through their 1.1.1.1 DNS resolver.

“They spelled out how their popularity algorithm is designed to reflect real human use and exclude automated traffic (they said they’re good at this),” Greenland wrote on LinkedIn. “So something has evidently gone wrong internally. We should have two rankings: one representing trust and real human use, and another derived from raw DNS volume.”

Why might it be a good idea to wholly separate malicious domains from the list? Greenland notes that Cloudflare Domain Rankings see widespread use for trust and safety determination, by browsers, DNS resolvers, safe browsing APIs and things like TRANCO.

“TRANCO is a respected open source list of the top million domains, and Cloudflare Radar is one of their five data providers,” he continued. “So there can be serious knock-on effects when a malicious domain features in Cloudflare’s top 10/100/1000/million. To many people and systems, the top 10 and 100 are naively considered safe and trusted, even though algorithmically-defined top-N lists will always be somewhat crude.”

Over this past week, Cloudflare started redacting portions of the malicious Aisuru domains from its Top Domains list, leaving only their domain suffix visible. Sometime in the past 24 hours, Cloudflare appears to have begun hiding the malicious Aisuru domains entirely from the web version of that list. However, downloading a spreadsheet of the current Top 200 domains from Cloudflare Radar shows an Aisuru domain still at the very top.

According to Cloudflare’s website, the majority of DNS queries to the top Aisuru domains — nearly 52 percent — originated from the United States. This tracks with my reporting from early October, which found Aisuru was drawing most of its firepower from IoT devices hosted on U.S. Internet providers like AT&T, Comcast and Verizon.

Experts tracking Aisuru say the botnet relies on well more than a hundred control servers, and that for the moment at least most of those domains are registered in the .su top-level domain (TLD). Dot-su is the TLD assigned to the former Soviet Union (.su’s Wikipedia page says the TLD was created just 15 months before the fall of the Berlin wall).

A Cloudflare blog post from October 27 found that .su had the highest “DNS magnitude” of any TLD, referring to a metric estimating the popularity of a TLD based on the number of unique networks querying Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 resolver. The report concluded that the top .su hostnames were associated with a popular online world-building game, and that more than half of the queries for that TLD came from the United States, Brazil and Germany [it’s worth noting that servers for the world-building game Minecraft were some of Aisuru’s most frequent targets].

A simple and crude way to detect Aisuru bot activity on a network may be to set an alert on any systems attempting to contact domains ending in .su. This TLD is frequently abused for cybercrime and by cybercrime forums and services, and blocking access to it entirely is unlikely to raise any legitimate complaints.