Say Hello To GoogleSQL

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Nearly half of the databases that public health officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were updating on a monthly basis have been frozen without notice or explanation, according to a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study—led by Janet Freilich, a law expert at Boston University, and Jeremy Jacobs, a medical professor at Vanderbilt University—examined the status of all CDC databases, finding a total of 82 that had, as of early 2025, been receiving updates at least monthly. But, of those 82, only 44 were still being regularly updated as of October 2025, with 38 (46 percent) having their updates paused without public notice or explanation.

Examining the databases' content, it appeared that vaccination data was most affected by the stealth data freezes. Of the 38 outdated databases, 33 (87 percent) included data related to vaccination. In contrast, none of the 44 still-updated databases relate to vaccination. Other frozen databases included data on infectious disease burden, such as data on hospitalizations from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

© Getty | Jim Watson

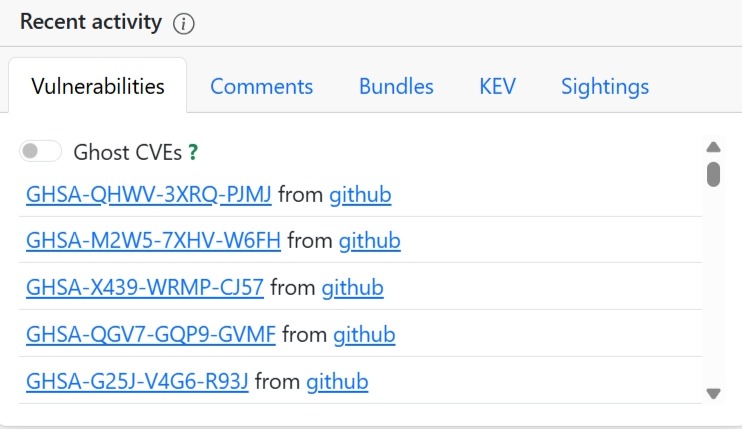

EU vulnerability database dashboard (Source: GCVE)[/caption]

The dashboard tracks more than identifiers. Weekly observations, comments, bundles, known exploited vulnerabilities (KEV), sightings, and even “ghost CVEs” are surfaced to show how issues evolve after disclosure. A rolling, month-long evolution view highlights how frequently vulnerabilities are seen, confirmed, exploited, or accompanied by proof-of-concept code.

Concrete examples illustrate the breadth of historical and current coverage. Widely known issues like CVE-2021-44228 (Log4Shell), CVE-2019-19781, CVE-2018-13379, and CVE-2017-17215 appear alongside recent entries such as CVE-2025-14847, CVE-2025-55182, CVE-2025-68613, and CVE-2025-59374. Older vulnerabilities, CVE-2015-2051 or CVE-2017-18368, sit next to newly published 2026 identifiers, reinforcing that the EU vulnerability database is designed for continuity, not just novelty.

EU vulnerability database dashboard (Source: GCVE)[/caption]

The dashboard tracks more than identifiers. Weekly observations, comments, bundles, known exploited vulnerabilities (KEV), sightings, and even “ghost CVEs” are surfaced to show how issues evolve after disclosure. A rolling, month-long evolution view highlights how frequently vulnerabilities are seen, confirmed, exploited, or accompanied by proof-of-concept code.

Concrete examples illustrate the breadth of historical and current coverage. Widely known issues like CVE-2021-44228 (Log4Shell), CVE-2019-19781, CVE-2018-13379, and CVE-2017-17215 appear alongside recent entries such as CVE-2025-14847, CVE-2025-55182, CVE-2025-68613, and CVE-2025-59374. Older vulnerabilities, CVE-2015-2051 or CVE-2017-18368, sit next to newly published 2026 identifiers, reinforcing that the EU vulnerability database is designed for continuity, not just novelty.