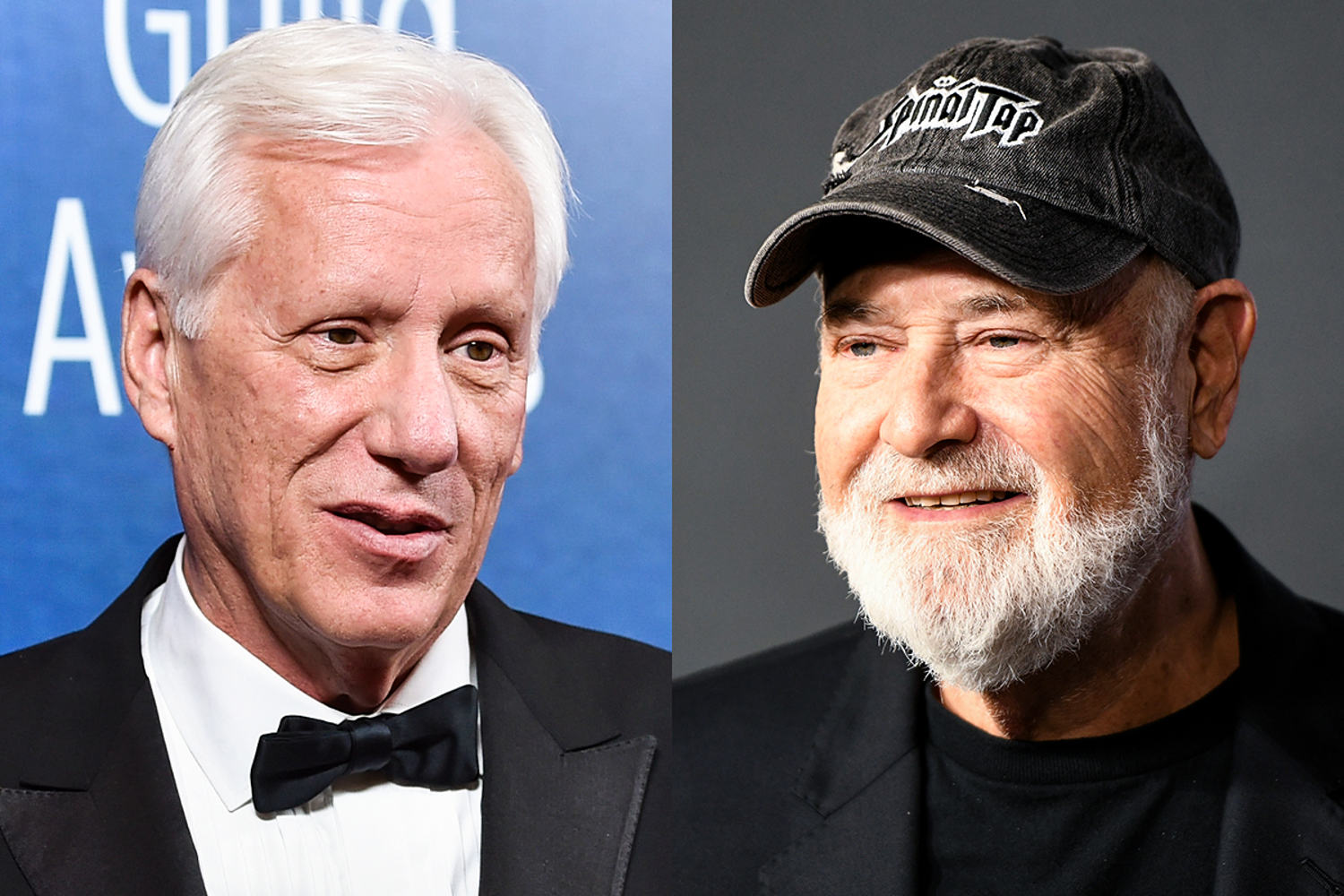

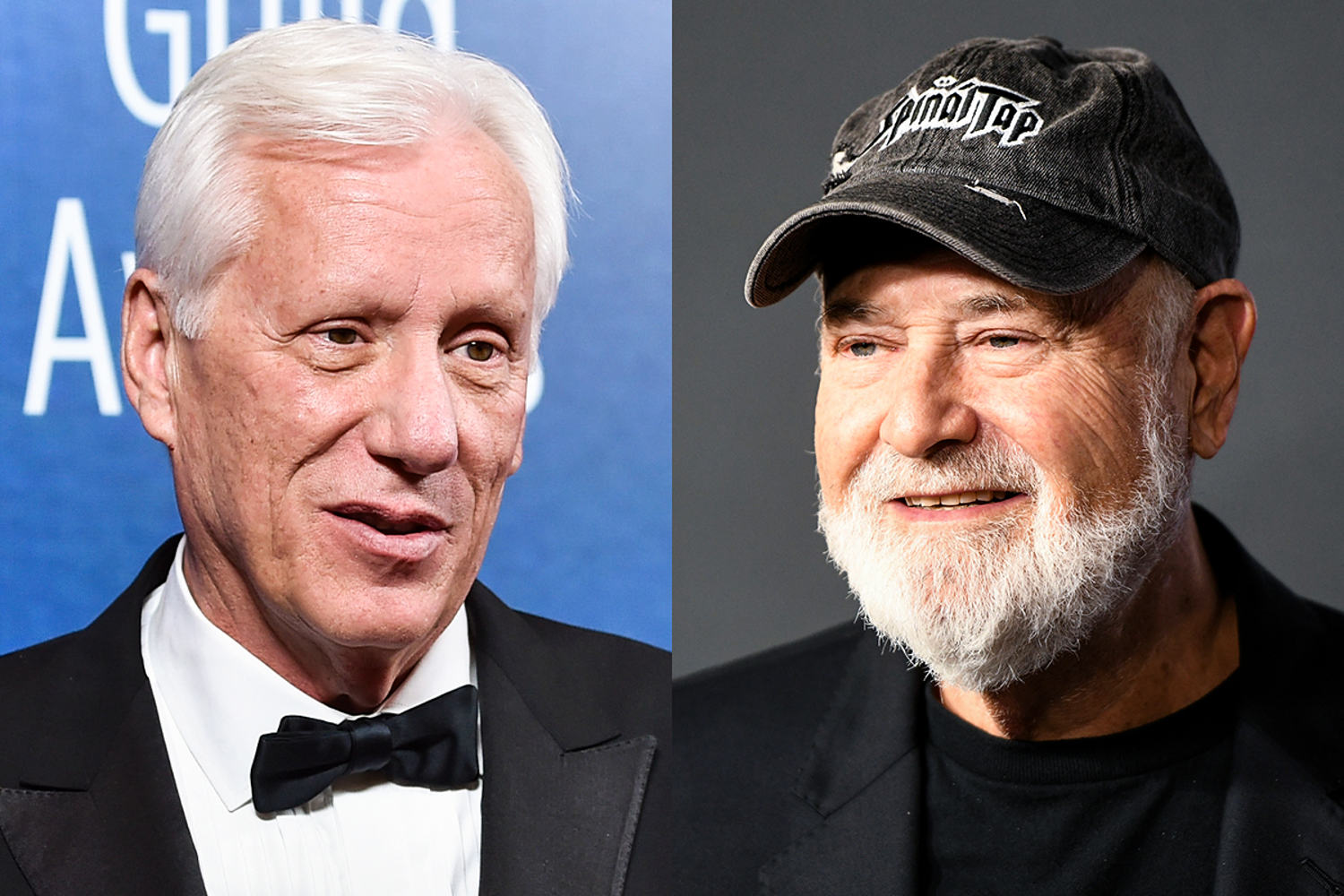

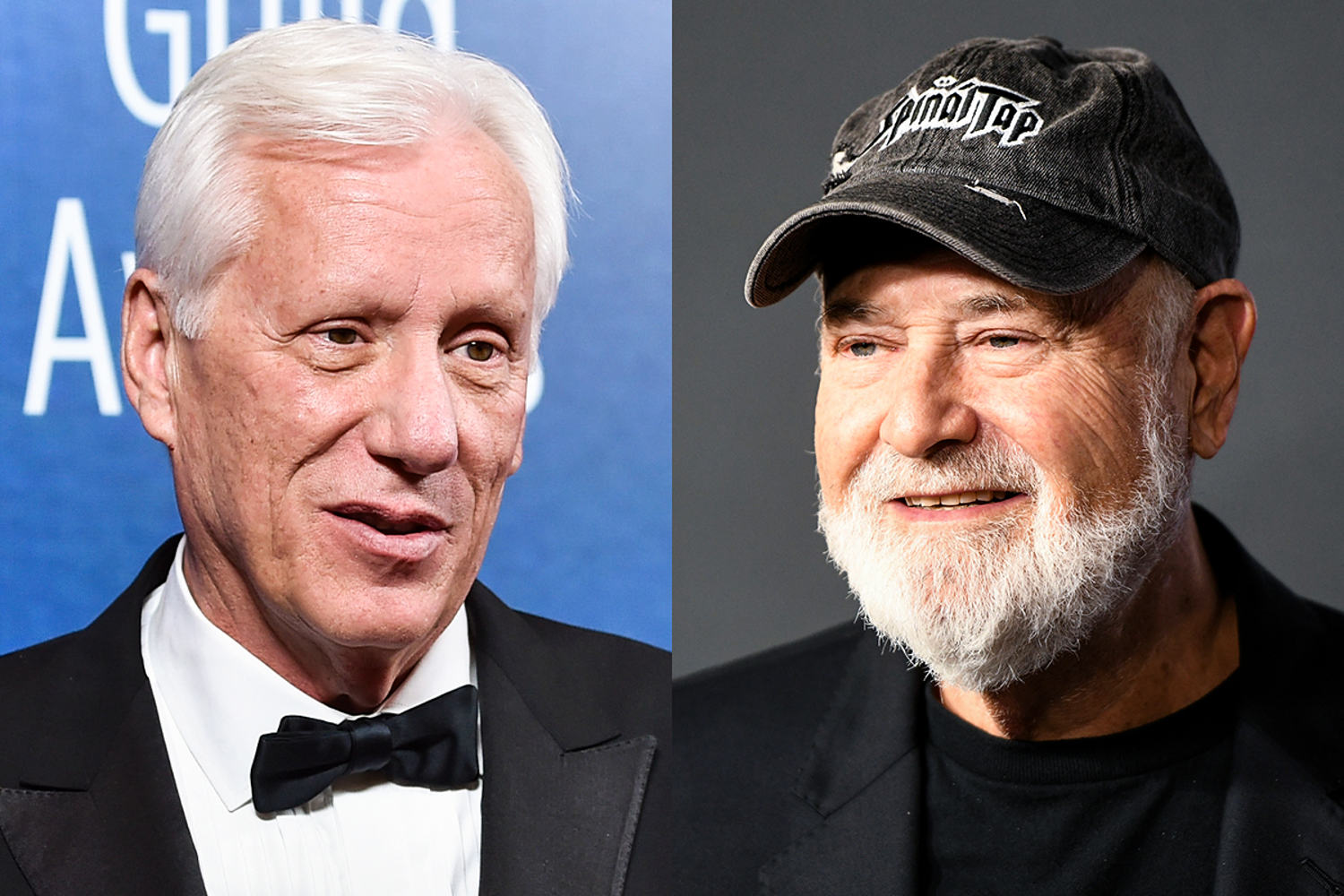

James Woods praises 'patriot' Rob Reiner, slams insults of slain director as 'infuriating'

© Columbia Pictures

© Columbia Pictures

© Columbia Pictures

Chromecasts were one of the most useful little gadgets that Google ever made, so of course it decided to ditch the product line. The Google Cast functionality lives on in the Google TV Streamer and Google TV devices and televisions, but sadly we won't see another Chromecast go on sale.

If you've got an older Chromecast hanging around, it'll still work fine for now. However, you might soon be moving on to a newer streaming device—or perhaps you already have—and that's left you wondering what to do with your older hardware. In fact, these small dongles are more versatile than you might have realized.

While streaming content from the likes of Netflix and Apple TV is going to be the primary use for these devices for most people, you can do plenty more with them—thanks to the casting support that Google and other developers have built into their apps.

If you've got a Chromecast-compatible security camera (including Google's Nest Cams), you can see a live feed on your Chromecast, making it easy to set up a mini security monitoring center if you have a smaller monitor or television somewhere to spare.

Getting the feed up on screen is as easy as saying "hey Google, show my..." followed by the camera name (as listed in the Google Home app). On the Chromecast with Google TV, you can also open the Google Home widget that appears on the main Settings pane.

Something else you can throw to a Chromecast in seconds: any tab you happen to have open in Google Chrome on your laptop or desktop. Just click the three dots in the top right corner of the tab, then choose Cast, Save and Share > Cast.

This means you can use the monitor or TV that your Chromecast is hooked up to as a second screen, with no cables required—just a wifi network.

When it comes to slinging content to your TV screen, you're going to think about movies and shows first and foremost, but the Google Cast standard works with audio apps as well—including the likes of Spotify, Pocket Casts, and Audible.

This is especially worth looking into if you've got a soundbar or a high-end speaker system connected to your television, because it means you can enjoy your audio streams at a much higher volume and a much higher level of quality, compared to your phone.

This one needs a Chromecast with local storage installed, so I'm primarily talking about the Chromecast with Google TV. That device supports local apps, which means it also lets you set up games to play with the remote or a connected Bluetooth controller.

See what you can find by browsing the Google Play Store, but Super Macro 64 showcases 25 different titles you can play easily, while the folks at XDA Developers have put together a full guide to creating a retro game emulator with the help of RetroArch.

Chromecasts work great as a way to add some ambience to a room when you're not actually watching something on a TV or monitor. You can show your own personal pictures, or a selection of nature shots, or pretty much anything you want.

Either cast via Google Photos (open an album, tap the three dots in the top right corner, then Cast), or set up a screensaver through the Google Home app. Select your Chromecast, tap the gear icon (top right), then choose Ambient mode.

Trying to hold video calls—whether with family over the holidays or colleagues during a meeting—isn't always easy on a phone screen or even a laptop screen, so why not take advantage of a larger monitor or TV with a Chromecast plugged into it?

For this to work you need to be using Google Meet in a web browser on a computer. You can either choose the "cast this meeting" option before it starts, or click the three dots during the meeting (Google has full instructions online).

The Zen-like US representative from Minnesota has had the highest level of death threats of any congressperson because of the president’s attacks

“That’s Teddy,” said Tim Mynett, husband of the US representative Ilhan Omar, as their five-year-old labrador retriever capered around her office on Capitol Hill. “If you make too much eye contact, he’ll lose it. He’s my best friend – and he’s our security detail these days.”

The couple were sitting on black leather furniture around a coffee table. Apart from a sneezing fit that took her husband by surprise, Omar had an unusual Zen-like calm for someone who receives frequent death threats and is the subject of a vendetta from the most powerful man in the world.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Caroline Gutman/The Guardian

© Photograph: Caroline Gutman/The Guardian

© Photograph: Caroline Gutman/The Guardian

Puccini’s opera returns to Covent Garden in a vivid staging that, although 40 years old, still feels fresh and fun. David Levene had exclusive access to rehearsals to witness the severed heads, the sumptuous costumes – and the executioner going green

Andrei Șerban’s staging, with dazzling designs by Sally Jacobs, made its debut in 1984 and is the Royal Opera’s longest-running production. This is its 19th revival: the performance on 18 December will be its 295th at Covent Garden. Turandot tackles grand emotions and even grander themes: love, fear, devotion, power, loyalty, life and death in a fantastical, fairytale version of imperial China. And, of course, there’s surely opera’s most famous moment, the showstopper aria Nessun Dorma.

“If the opera has depths, Șerban is content to ignore them, but for once it doesn’t seem to matter. The three-storey Chinese pagoda set, army of extras and troupe of masked dancers make his cartoon-coloured creation the nearest the company has to a West End spectacular,” wrote the Guardian’s Erica Jeal reviewing a 2005 revival.

Puccini’s libretto states that the emperor appears among “clouds of incense … among the clouds like a god”. In this production he does indeed appear as if from the heavens, his magnificent throne lowered slowly to the ground.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian

© Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian

© Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian

Our cartoonist on exorbitant World Cup ticket prices and peace breaking out on Merseyside

Continue reading...

© Illustration: David Squires/The Guardian

© Illustration: David Squires/The Guardian

© Illustration: David Squires/The Guardian

The actor looks back on his first foray as producer as the Oscar-winning drama reaches its 50th anniversary

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest at 50: the spirit of rebellion lives on

His early career was defined by the Vietnam war with early roles in political films such as Hail, Hero! and Summertree. So it felt natural for Michael Douglas, just 31, to make his first foray into producing with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a tale of one man raging against the system.

Fifty years since its release, Douglas is struck how Cuckoo’s Nest resonates anew in today’s landscape. “It’s about as classic a story as we’ll ever have and it seems timeless now, with what’s going on in our country politically, about man versus the machine and individuality versus the corporate world,” the 81-year-old says via Zoom from Santa Barbara, California.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Snap/Shutterstock

© Photograph: Snap/Shutterstock

© Photograph: Snap/Shutterstock

Generative AI has advanced to the stage where you can ask bots such as ChatGPT or Gemini questions about almost anything, and get reasonable-sounding responses—and now renowned gadget repair site iFixit has joined the party with an AI assistant of its own, ready and willing to solve any of your hardware problems.

While you can already ask general-purpose chatbots for advice on how to repair a phone screen or diagnose a problem with a car engine, there's always the question of how accurate the AI replies will be. With FixBot, iFixit is trying to minimize mistakes by drawing on its vast library of verified repair guides, written by experts and users.

That's certainly reassuring: I don't want to waste time and money replacing a broken phone screen with a new display that's the wrong size or shape. And using a conversational AI bot to fix gadget problems is often going to feel like a more natural and intuitive experience than a Google search. As iFixit puts it, the bot "does what a good expert does" in guiding you to the right solutions.

The iFixit website has been around since 2003—practically ancient times, considering the rapid evolution of modern technology. The iFixit team has always prided itself on detailed, thorough, tested guides to repairing devices, and all of that information can now be tapped into by the FixBot tool.

iFixit says the bot is trained on more than 125,000 repair guides written by humans who have worked through the steps involved, as well as the question and answer forums attached to the site, and the "huge cache" of PDF manuals that iFixit has accumulated over the years that it's been business.

That gives me a lot more confidence that FixBot will get its answers right, compared to whatever ChatGPT or Gemini might tell me. iFixit hasn't said what AI models are powering the bot—only that they've been "hand-picked"—and there's also a custom-built search engine included to select data sources from the repair archives on the site.

"Every answer starts with a search for guides, parts, and repairs that worked," according to the iFixit team, and that conversational approach you'll recognize from other AI bots is here too: If you need clarification on something, then you can ask a follow-up question. In the same way, if the AI bot needs more information or specifics, it will ask you.

It's designed to be fast—responses should be returned in seconds—and the iFixit team also talks about an "evaluation harness" that tests the FixBot responses against thousands of real repair questions posed and answered by humans. That extra level of fact-checking should reduce the number of false answers you get.

However, it's not perfect, as iFixit admits: "FixBot is an AI, and AI sometimes gets things wrong." Whether or not those mistakes will be easy to spot remains to be seen, but users of the chatbot are being encouraged to upload their own documents and repair solutions to fix gaps in the knowledge that FixBot is drawing on.

iFixit says the FixBot is going to be free for everyone to use, for a limited time. At some point, there will be a free version with limitations, and paid tiers with the full set of features—including support for voice input and document uploads. You can give it a try for yourself now on the iFixit website.

I was reluctant to deliberately break one of my devices just so FixBot could help me repair it, but I did test it with a few issues I've had (and sorted out) in the past. One was a completely dead SSD drive stopping my Windows PC from booting: I started off with a vague description about the computer not starting up properly, and the bot did a good job at narrowing down what the problem was, and suggesting fixes.

It went through everything I had already tried when the problem happened, including trying System Repair and troubleshooting the issue via the Command Prompt. Eventually, via a few links to repair guides on the iFixit website, it did conclude that my SSD drive had been corrupted by a power cut—which I knew was what had indeed happened.

I also tested the bot with a more general question about a phone restarting at random times—something one of my old handsets used to do. Again, the responses were accurate, and the troubleshooting steps I was asked to try made a lot of sense. I was also directed to the iFixit guide for the phone model.

The bot is as enthusiastic as a lot of the others available now (I was regularly praised for the "excellent information" I was providing), and does appear to know what it's talking about. This is one of the scenarios where generative AI shows its worth, in distilling a large amount of information based on natural language prompts.

There's definitely potential here: Compare this approach to having to sift through dozens of forum posts, web articles, and documents manually. However, there's always that nagging sense that AI makes mistakes, as the on-screen FixBot disclaimer says. I'd recommend checking other sources before doing anything drastic with your hardware troubleshooting.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

The Age of Disclosure was granted a Capitol Hill screening and has broken digital rental records but does it really offer proof of alien life?

It has been hailed as a game changer in public attitudes towards UFOs, ending a culture of silence around claims once dismissed as the preserve of conspiracy theorists and crackpots.

The Age of Disclosure has been boosted in its effort to shift the conversation about extraterrestrials from the fringe to the mainstream with a Capitol Hill screening and considerable commercial success. It broke the record for highest-grossing documentary on Amazon’s Prime Video within 48 hours of its release, Deadline reported this week.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: 'Age of Disclosure'

© Photograph: 'Age of Disclosure'

© Photograph: 'Age of Disclosure'

The Welsh author vividly captures the solitude, hard labour, dramas and dangers of rural life

In these six stories of human frailty and responsibility, Welsh writer Cynan Jones explores the imperatives of love and the labour of making and sustaining lives. Each is told with a compelling immediacy and intensity, and with the quality of returning to a memory.

In the story Reindeer a man is seeking a bear, which has been woken by hunger from hibernation and is now raiding livestock from the farms of a small isolated community. “There was no true sunshine. There was no gleam in the snow, but the lateness of the left daylight put a cold faint blue through the slopes.” The story’s world is one in which skill, endurance, even stubbornness might be insufficient to succeed, but are just enough to persist.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Mark Newman/Getty Images

© Photograph: Mark Newman/Getty Images

© Photograph: Mark Newman/Getty Images

The microwave-size instrument at Lila Sciences in Cambridge, Massachusetts, doesn’t look all that different from others that I’ve seen in state-of-the-art materials labs. Inside its vacuum chamber, the machine zaps a palette of different elements to create vaporized particles, which then fly through the chamber and land to create a thin film, using a technique called sputtering. What sets this instrument apart is that artificial intelligence is running the experiment; an AI agent, trained on vast amounts of scientific literature and data, has determined the recipe and is varying the combination of elements.

Later, a person will walk the samples, each containing multiple potential catalysts, over to a different part of the lab for testing. Another AI agent will scan and interpret the data, using it to suggest another round of experiments to try to optimize the materials’ performance.

This story is part of MIT Technology Review’s Hype Correction package, a series that resets expectations about what AI is, what it makes possible, and where we go next.

For now, a human scientist keeps a close eye on the experiments and will approve the next steps on the basis of the AI’s suggestions and the test results. But the startup is convinced this AI-controlled machine is a peek into the future of materials discovery—one in which autonomous labs could make it far cheaper and faster to come up with novel and useful compounds.

Flush with hundreds of millions of dollars in new funding, Lila Sciences is one of AI’s latest unicorns. The company is on a larger mission to use AI-run autonomous labs for scientific discovery—the goal is to achieve what it calls scientific superintelligence. But I’m here this morning to learn specifically about the discovery of new materials.

We desperately need better materials to solve our problems. We’ll need improved electrodes and other parts for more powerful batteries; compounds to more cheaply suck carbon dioxide out of the air; and better catalysts to make green hydrogen and other clean fuels and chemicals. And we will likely need novel materials like higher-temperature superconductors, improved magnets, and different types of semiconductors for a next generation of breakthroughs in everything from quantum computing to fusion power to AI hardware.

But materials science has not had many commercial wins in the last few decades. In part because of its complexity and the lack of successes, the field has become something of an innovation backwater, overshadowed by the more glamorous—and lucrative—search for new drugs and insights into biology.

The idea of using AI for materials discovery is not exactly new, but it got a huge boost in 2020 when DeepMind showed that its AlphaFold2 model could accurately predict the three-dimensional structure of proteins. Then, in 2022, came the success and popularity of ChatGPT. The hope that similar AI models using deep learning could aid in doing science captivated tech insiders. Why not use our new generative AI capabilities to search the vast chemical landscape and help simulate atomic structures, pointing the way to new substances with amazing properties?

“Simulations can be super powerful for framing problems and understanding what is worth testing in the lab. But there’s zero problems we can ever solve in the real world with simulation alone.”

John Gregoire, Lila Sciences, chief autonomous science officer

Researchers touted an AI model that had reportedly discovered “millions of new materials.” The money began pouring in, funding a host of startups. But so far there has been no “eureka” moment, no ChatGPT-like breakthrough—no discovery of new miracle materials or even slightly better ones.

The startups that want to find useful new compounds face a common bottleneck: By far the most time-consuming and expensive step in materials discovery is not imagining new structures but making them in the real world. Before trying to synthesize a material, you don’t know if, in fact, it can be made and is stable, and many of its properties remain unknown until you test it in the lab.

“Simulations can be super powerful for kind of framing problems and understanding what is worth testing in the lab,” says John Gregoire, Lila Sciences’ chief autonomous science officer. “But there’s zero problems we can ever solve in the real world with simulation alone.”

Startups like Lila Sciences have staked their strategies on using AI to transform experimentation and are building labs that use agents to plan, run, and interpret the results of experiments to synthesize new materials. Automation in laboratories already exists. But the idea is to have AI agents take it to the next level by directing autonomous labs, where their tasks could include designing experiments and controlling the robotics used to shuffle samples around. And, most important, companies want to use AI to vacuum up and analyze the vast amount of data produced by such experiments in the search for clues to better materials.

If they succeed, these companies could shorten the discovery process from decades to a few years or less, helping uncover new materials and optimize existing ones. But it’s a gamble. Even though AI is already taking over many laboratory chores and tasks, finding new—and useful—materials on its own is another matter entirely.

I have been reporting about materials discovery for nearly 40 years, and to be honest, there have been only a few memorable commercial breakthroughs, such as lithium-ion batteries, over that time. There have been plenty of scientific advances to write about, from perovskite solar cells to graphene transistors to metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), materials based on an intriguing type of molecular architecture that recently won its inventors a Nobel Prize. But few of those advances—including MOFs—have made it far out of the lab. Others, like quantum dots, have found some commercial uses, but in general, the kinds of life-changing inventions created in earlier decades have been lacking.

Blame the amount of time (typically 20 years or more) and the hundreds of millions of dollars it takes to make, test, optimize, and manufacture a new material—and the industry’s lack of interest in spending that kind of time and money in low-margin commodity markets. Or maybe we’ve just run out of ideas for making stuff.

The need to both speed up that process and find new ideas is the reason researchers have turned to AI. For decades, scientists have used computers to design potential materials, calculating where to place atoms to form structures that are stable and have predictable characteristics. It’s worked—but only kind of. Advances in AI have made that computational modeling far faster and have promised the ability to quickly explore a vast number of possible structures. Google DeepMind, Meta, and Microsoft have all launched efforts to bring AI tools to the problem of designing new materials.

But the limitations that have always plagued computational modeling of new materials remain. With many types of materials, such as crystals, useful characteristics often can’t be predicted solely by calculating atomic structures.

To uncover and optimize those properties, you need to make something real. Or as Rafael Gómez-Bombarelli, one of Lila’s cofounders and an MIT professor of materials science, puts it: “Structure helps us think about the problem, but it’s neither necessary nor sufficient for real materials problems.”

Perhaps no advance exemplified the gap between the virtual and physical worlds more than DeepMind’s announcement in late 2023 that it had used deep learning to discover “millions of new materials,” including 380,000 crystals that it declared “the most stable, making them promising candidates for experimental synthesis.” In technical terms, the arrangement of atoms represented a minimum energy state where they were content to stay put. This was “an order-of-magnitude expansion in stable materials known to humanity,” the DeepMind researchers proclaimed.

To the AI community, it appeared to be the breakthrough everyone had been waiting for. The DeepMind research not only offered a gold mine of possible new materials, it also created powerful new computational methods for predicting a large number of structures.

But some materials scientists had a far different reaction. After closer scrutiny, researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said they’d found “scant evidence for compounds that fulfill the trifecta of novelty, credibility, and utility.” In fact, the scientists reported, they didn’t find any truly novel compounds among the ones they looked at; some were merely “trivial” variations of known ones. The scientists appeared particularly peeved that the potential compounds were labeled materials. They wrote: “We would respectfully suggest that the work does not report any new materials but reports a list of proposed compounds. In our view, a compound can be called a material when it exhibits some functionality and, therefore, has potential utility.”

Some of the imagined crystals simply defied the conditions of the real world. To do computations on so many possible structures, DeepMind researchers simulated them at absolute zero, where atoms are well ordered; they vibrate a bit but don’t move around. At higher temperatures—the kind that would exist in the lab or anywhere in the world—the atoms fly about in complex ways, often creating more disorderly crystal structures. A number of the so-called novel materials predicted by DeepMind appeared to be well-ordered versions of disordered ones that were already known.

More generally, the DeepMind paper was simply another reminder of how challenging it is to capture physical realities in virtual simulations—at least for now. Because of the limitations of computational power, researchers typically perform calculations on relatively few atoms. Yet many desirable properties are determined by the microstructure of the materials—at a scale much larger than the atomic world. And some effects, like high-temperature superconductivity or even the catalysis that is key to many common industrial processes, are far too complex or poorly understood to be explained by atomic simulations alone.

Even so, there are signs that the divide between simulations and experimental work is beginning to narrow. DeepMind, for one, says that since the release of the 2023 paper it has been working with scientists in labs around the world to synthesize AI-identified compounds and has achieved some success. Meanwhile, a number of the startups entering the space are looking to combine computational and experimental expertise in one organization.

One such startup is Periodic Labs, cofounded by Ekin Dogus Cubuk, a physicist who led the scientific team that generated the 2023 DeepMind headlines, and by Liam Fedus, a co-creator of ChatGPT at OpenAI. Despite its founders’ background in computational modeling and AI software, the company is building much of its materials discovery strategy around synthesis done in automated labs.

The vision behind the startup is to link these different fields of expertise by using large language models that are trained on scientific literature and able to learn from ongoing experiments. An LLM might suggest the recipe and conditions to make a compound; it can also interpret test data and feed additional suggestions to the startup’s chemists and physicists. In this strategy, simulations might suggest possible material candidates, but they are also used to help explain the experimental results and suggest possible structural tweaks.

The grand prize would be a room-temperature superconductor, a material that could transform computing and electricity but that has eluded scientists for decades.

Periodic Labs, like Lila Sciences, has ambitions beyond designing and making new materials. It wants to “create an AI scientist”—specifically, one adept at the physical sciences. “LLMs have gotten quite good at distilling chemistry information, physics information,” says Cubuk, “and now we’re trying to make it more advanced by teaching it how to do science—for example, doing simulations, doing experiments, doing theoretical modeling.”

The approach, like that of Lila Sciences, is based on the expectation that a better understanding of the science behind materials and their synthesis will lead to clues that could help researchers find a broad range of new ones. One target for Periodic Labs is materials whose properties are defined by quantum effects, such as new types of magnets. The grand prize would be a room-temperature superconductor, a material that could transform computing and electricity but that has eluded scientists for decades.

Superconductors are materials in which electricity flows without any resistance and, thus, without producing heat. So far, the best of these materials become superconducting only at relatively low temperatures and require significant cooling. If they can be made to work at or close to room temperature, they could lead to far more efficient power grids, new types of quantum computers, and even more practical high-speed magnetic-levitation trains.

The failure to find a room-temperature superconductor is one of the great disappointments in materials science over the last few decades. I was there when President Reagan spoke about the technology in 1987, during the peak hype over newly made ceramics that became superconducting at the relatively balmy temperature of 93 Kelvin (that’s −292 °F), enthusing that they “bring us to the threshold of a new age.” There was a sense of optimism among the scientists and businesspeople in that packed ballroom at the Washington Hilton as Reagan anticipated “a host of benefits, not least among them a reduced dependence on foreign oil, a cleaner environment, and a stronger national economy.” In retrospect, it might have been one of the last times that we pinned our economic and technical aspirations on a breakthrough in materials.

The promised new age never came. Scientists still have not found a material that becomes superconducting at room temperatures, or anywhere close, under normal conditions. The best existing superconductors are brittle and tend to make lousy wires.

One of the reasons that finding higher-temperature superconductors has been so difficult is that no theory explains the effect at relatively high temperatures—or can predict it simply from the placement of atoms in the structure. It will ultimately fall to lab scientists to synthesize any interesting candidates, test them, and search the resulting data for clues to understanding the still puzzling phenomenon. Doing so, says Cubuk, is one of the top priorities of Periodic Labs.

It can take a researcher a year or more to make a crystal structure for the first time. Then there are typically years of further work to test its properties and figure out how to make the larger quantities needed for a commercial product.

Startups like Lila Sciences and Periodic Labs are pinning their hopes largely on the prospect that AI-directed experiments can slash those times. One reason for the optimism is that many labs have already incorporated a lot of automation, for everything from preparing samples to shuttling test items around. Researchers routinely use robotic arms, software, automated versions of microscopes and other analytical instruments, and mechanized tools for manipulating lab equipment.

The automation allows, among other things, for high-throughput synthesis, in which multiple samples with various combinations of ingredients are rapidly created and screened in large batches, greatly speeding up the experiments.

The idea is that using AI to plan and run such automated synthesis can make it far more systematic and efficient. AI agents, which can collect and analyze far more data than any human possibly could, can use real-time information to vary the ingredients and synthesis conditions until they get a sample with the optimal properties. Such AI-directed labs could do far more experiments than a person and could be far smarter than existing systems for high-throughput synthesis.

But so-called self-driving labs for materials are still a work in progress.

Many types of materials require solid-state synthesis, a set of processes that are far more difficult to automate than the liquid-handling activities that are commonplace in making drugs. You need to prepare and mix powders of multiple inorganic ingredients in the right combination for making, say, a catalyst and then decide how to process the sample to create the desired structure—for example, identifying the right temperature and pressure at which to carry out the synthesis. Even determining what you’ve made can be tricky.

In 2023, the A-Lab at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory claimed to be the first fully automated lab to use inorganic powders as starting ingredients. Subsequently, scientists reported that the autonomous lab had used robotics and AI to synthesize and test 41 novel materials, including some predicted in the DeepMind database. Some critics questioned the novelty of what was produced and complained that the automated analysis of the materials was not up to experimental standards, but the Berkeley researchers defended the effort as simply a demonstration of the autonomous system’s potential.

“How it works today and how we envision it are still somewhat different. There’s just a lot of tool building that needs to be done,” says Gerbrand Ceder, the principal scientist behind the A-Lab.

AI agents are already getting good at doing many laboratory chores, from preparing recipes to interpreting some kinds of test data—finding, for example, patterns in a micrograph that might be hidden to the human eye. But Ceder is hoping the technology could soon “capture human decision-making,” analyzing ongoing experiments to make strategic choices on what to do next. For example, his group is working on an improved synthesis agent that would better incorporate what he calls scientists’ “diffused” knowledge—the kind gained from extensive training and experience. “I imagine a world where people build agents around their expertise, and then there’s sort of an uber-model that puts it together,” he says. “The uber-model essentially needs to know what agents it can call on and what they know, or what their expertise is.”

“In one field that I work in, solid-state batteries, there are 50 papers published every day. And that is just one field that I work in. The A I revolution is about finally gathering all the scientific data we have.”

Gerbrand Ceder, principal scientist, A-Lab

One of the strengths of AI agents is their ability to devour vast amounts of scientific literature. “In one field that I work in, solid-state batteries, there are 50 papers published every day. And that is just one field that I work in,” says Ceder. It’s impossible for anyone to keep up. “The AI revolution is about finally gathering all the scientific data we have,” he says.

Last summer, Ceder became the chief science officer at an AI materials discovery startup called Radical AI and took a sabbatical from the University of California, Berkeley, to help set up its self-driving labs in New York City. A slide deck shows the portfolio of different AI agents and generative models meant to help realize Ceder’s vision. If you look closely, you can spot an LLM called the “orchestrator”—it’s what CEO Joseph Krause calls the “head honcho.”

So far, despite the hype around the use of AI to discover new materials and the growing momentum—and money—behind the field, there still has not been a convincing big win. There is no example like the 2016 victory of DeepMind’s AlphaGo over a Go world champion. Or like AlphaFold’s achievement in mastering one of biomedicine’s hardest and most time-consuming chores, predicting 3D structures of proteins.

The field of materials discovery is still waiting for its moment. It could come if AI agents can dramatically speed the design or synthesis of practical materials, similar to but better than what we have today. Or maybe the moment will be the discovery of a truly novel one, such as a room-temperature superconductor.

With or without such a breakthrough moment, startups face the challenge of trying to turn their scientific achievements into useful materials. The task is particularly difficult because any new materials would likely have to be commercialized in an industry dominated by large incumbents that are not particularly prone to risk-taking.

Susan Schofer, a tech investor and partner at the venture capital firm SOSV, is cautiously optimistic about the field. But Schofer, who spent several years in the mid-2000s as a catalyst researcher at one of the first startups using automation and high-throughput screening for materials discovery (it didn’t survive), wants to see some evidence that the technology can translate into commercial successes when she evaluates startups to invest in.

In particular, she wants to see evidence that the AI startups are already “finding something new, that’s different, and know how they are going to iterate from there.” And she wants to see a business model that captures the value of new materials. She says, “I think the ideal would be: I got a spec from the industry. I know what their problem is. We’ve defined it. Now we’re going to go build it. Now we have a new material that we can sell, that we have scaled up enough that we’ve proven it. And then we partner somehow to manufacture it, but we get revenue off selling the material.”

Schofer says that while she gets the vision of trying to redefine science, she’d advise startups to “show us how you’re going to get there.” She adds, “Let’s see the first steps.”

Demonstrating those first steps could be essential in enticing large existing materials companies to embrace AI technologies more fully. Corporate researchers in the industry have been burned before—by the promise over the decades that increasingly powerful computers will magically design new materials; by combinatorial chemistry, a fad that raced through materials R&D labs in the early 2000s with little tangible result; and by the promise that synthetic biology would make our next generation of chemicals and materials.

More recently, the materials community has been blanketed by a new hype cycle around AI. Some of that hype was fueled by the 2023 DeepMind announcement of the discovery of “millions of new materials,” a claim that, in retrospect, clearly overpromised. And it was further fueled when an MIT economics student posted a paper in late 2024 claiming that a large, unnamed corporate R&D lab had used AI to efficiently invent a slew of new materials. AI, it seemed, was already revolutionizing the industry.

A few months later, the MIT economics department concluded that “the paper should be withdrawn from public discourse.” Two prominent MIT economists who are acknowledged in a footnote in the paper added that they had “no confidence in the provenance, reliability or validity of the data and the veracity of the research.”

Can AI move beyond the hype and false hopes and truly transform materials discovery? Maybe. There is ample evidence that it’s changing how materials scientists work, providing them—if nothing else—with useful lab tools. Researchers are increasingly using LLMs to query the scientific literature and spot patterns in experimental data.

But it’s still early days in turning those AI tools into actual materials discoveries. The use of AI to run autonomous labs, in particular, is just getting underway; making and testing stuff takes time and lots of money. The morning I visited Lila Sciences, its labs were largely empty, and it’s now preparing to move into a much larger space a few miles away. Periodic Labs is just beginning to set up its lab in San Francisco. It’s starting with manual synthesis guided by AI predictions; its robotic high-throughput lab will come soon. Radical AI reports that its lab is almost fully autonomous but plans to soon move to a larger space.

When I talk to the scientific founders of these startups, I hear a renewed excitement about a field that long operated in the shadows of drug discovery and genomic medicine. For one thing, there is the money. “You see this enormous enthusiasm to put AI and materials together,” says Ceder. “I’ve never seen this much money flow into materials.”

Reviving the materials industry is a challenge that goes beyond scientific advances, however. It means selling companies on a whole new way of doing R&D.

But the startups benefit from a huge dose of confidence borrowed from the rest of the AI industry. And maybe that, after years of playing it safe, is just what the materials business needs.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Rights groups dismiss ‘sham conviction’ of media tycoon on national security offences in city’s most closely watched rulings in decades

Jimmy Lai, the Hong Kong pro-democracy media tycoon, is facing life in prison after being found guilty of national security and sedition offences, in one of the most closely watched rulings since the city’s return to Chinese rule in 1997.

Soon after the ruling was delivered, rights and press groups decried the verdict as a “sham conviction” and an attack on press freedom.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Leung Man Hei/AFP/Getty Images

© Photograph: Leung Man Hei/AFP/Getty Images

© Photograph: Leung Man Hei/AFP/Getty Images

Progressing from child labourer to billionaire, Lai used his power and wealth to promote democracy, which ultimately pitted him against authorities in Beijing

On Monday, a Hong Kong court convicted Jimmy Lai of national security offences, the end to a landmark trial for the city and its hobbled protest movement.

The verdict was expected. Long a thorn in the side of Beijing, Lai, a 78-year-old media tycoon and activist, was a primary target of the most recent and definitive crackdown on Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. Authorities cast him as a traitor and a criminal.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters

© Photograph: Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters

© Photograph: Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

The president announces non-existent emergencies to invoke extraordinary powers – and neutralizes the opposition

This month, we learned that, in the course of bombing a boat of suspected drug smugglers, the US military intentionally killed two survivors clinging to the wreckage after its initial air assault. In addition, Donald Trump said it was seditious for Democratic members of Congress to inform members of the military that they can, and indeed, must, resist patently illegal orders, and the FBI and Pentagon are reportedly investigating the members’ speech. Those related developments – the murder of civilians and an attack on free speech – exemplify two of Trump’s principal tactics in his second term. The first involves the assertion of extraordinary emergency powers in the absence of any actual emergency. The second seeks to suppress dissent by punishing those who dare to raise their voices. Both moves have been replicated time and time again since January 2025. How courts and the public respond will determine the future of constitutional democracy in the United States.

Nothing is more essential to a liberal democracy than the rule of law – that is, the notion that a democratic government is guided by laws, not discretionary whims; that the laws respect basic liberties for all; and that independent courts have the authority to hold political officials accountable when they violate those laws. These principles, forged in the United Kingdom, adopted and revised by the United States, are the bedrock of constitutional democracy. But they depend on courts being willing and able to check government abuse, and citizens exercising their rights to speak out in defense of the fundamental values when those values are under attack.

David Cole is the Honorable George J Mitchell professor in law and public policy at Georgetown University and former national legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union. This essay is adapted from his international rule of law lecture sponsored by the Bar Council.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Alex Brandon/AP

© Photograph: Alex Brandon/AP

© Photograph: Alex Brandon/AP

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

No easy games? Surely this one would be for Arsenal. Never before in English football history had a team endured a worse league record after 15 matches than Wolves. In any of the professional divisions. Their haul of two points gave an outline of the grimness, although by no means all of the detail.

Before kick-off, the bookmakers had Wolves at 28-1 to win; it was 8-1 for the draw. You just had to hand it to the club’s 3,000 travelling fans who took up their full ticket allocation. There were no trains back to Wolverhampton after the game, obviously. It was a weekend. Mission impossible? This felt like the definition of it.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: David Price/Arsenal FC/Getty Images

© Photograph: David Price/Arsenal FC/Getty Images

© Photograph: David Price/Arsenal FC/Getty Images

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

US president finds himself shouldering same burdens of affordability crisis and the inexorable march of time

He was supposed to be touting the economy but could not resist taking aim at an old foe. “Which is better: Sleepy Joe or Crooked Joe?” Donald Trump teased supporters in Pennsylvania this week, still toying with nicknames for his predecessor Joe Biden. “Typically, Crooked Joe wins. I’m surprised because to me he’s a sleepy son of a bitch.”

Exulting in Biden’s drowsiness, the US president and his supporters seemed blissfully ignorant of a rich irony: that 79-year-old Trump himself has recently been spotted apparently dozing off at various meetings.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Alex Wong/Getty Images

© Photograph: Alex Wong/Getty Images

© Photograph: Alex Wong/Getty Images

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

The writer’s former partner and her co-star Ruby Ashbourne Serkis describe the bittersweet nature of remounting his 90s play so soon after his death

• ‘We were swimming in the mind pool of Tom Stoppard!’ – actors salute the great playwright

I won’t, I promise, refer to Felicity Kendal as Tom Stoppard’s muse. “No,” she says firmly. “Not this week.” Speaking to Stoppard’s former partner and longtime leading lady is delicate in the immediate aftermath of the writer’s death. But she is previewing a revival of his Indian Ink, so he shimmers through the conversation. The way Kendal refers to Stoppard in the present tense tells its own poignant story.

Settling into a squishy brown sofa at Hampstead theatre, Kendal describes revisiting the 1995 work, developed from a 1991 radio play. “It’s a play that I always thought I’d like to go back to.” Previously starring as Flora Crewe, a provocative British poet visiting 1930s India, she now plays Eleanor Swan, Flora’s sister. We meet Eleanor in the 1980s, fending off an intrusive biographer but uncovering her sister’s rapt and nuanced relationships in India.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Johan Persson

© Photograph: Johan Persson

© Photograph: Johan Persson

With its soaring ceilings, meandering pathways and mesh-like walls, Taichung Art Museum, designed by Sanaa, sweeps visitors from library to gallery to rooftop garden for rousing views

Walking through the brand new Taichung Art Museum in central Taiwan, directions are kind of an abstract concept. Designed by powerhouse Japanese architecture firm Sanaa, the complex is a collection of eight askew buildings, melding an art museum and municipal library, encased in silver mesh-like walls, with soaring ceilings and meandering pathways.

Past the lobby – a breezy open space that is neither inside nor out – the visitor wanders around paths and ramps, finding themselves in the library one minute and a world-class art exhibition the next. A door might suddenly step through to a skybridge over a rooftop garden, with sweeping views across Taichung’s Central Park, or into a cosy teenage reading room. Staircases float on the outside of buildings, floor levels are disparate, complementing a particular space’s purpose and vibe rather than having an overall consistency.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Iwan Baan/Image courtesy of Cultural Affairs Bureau, Taichung City Government. © Iwan Baan

© Photograph: Iwan Baan/Image courtesy of Cultural Affairs Bureau, Taichung City Government. © Iwan Baan

© Photograph: Iwan Baan/Image courtesy of Cultural Affairs Bureau, Taichung City Government. © Iwan Baan

We may earn a commission from links on this page.

Philips Hue is one of the most well-respected and popular brands in smart lights—but what about its smart security cameras? Parent company Signify has been developing Hue cameras for a couple of years now, with a video doorbell and 2K camera upgrades recently added to the portfolio of devices. (Note: This 2K version hasn't yet landed in the U.S., but the existing 1080p versions are quite similar.)

I got a chance to test out the new 2K Hue Secure camera, and alongside all the basics of a camera like this, it came with an extra bonus that worked better than I expected: seamless integration with Philips Hue lights. These two product categories actually work better together than you might think.

While you can certainly connect cameras and lights across a variety of smart home platforms, Philips Hue is one of very few manufacturers making both types of device (TP-Link is another). That gives you a simplicity and interoperability you don't really get elsewhere.

Hue cameras are controlled inside the same Hue app for Android or iOS as the Hue lights. You don't necessarily need a Hue Bridge to connect the camera, too, as it can link to your wifi directly, but the Bridge is required if you want it to be able to sync with your lights—which is one of the key features here. (If you already have the lights, you'll already have the Bridge anyway.)

The 2K Hue Secure wired camera I've been testing comes with a 2K video resolution (as the name suggests). two-way audio, a built-in siren, infrared night vision, and weatherproofing (so you can use it indoors or out). As well as the wired version I've got here, there's also a battery-powered option, and a model that comes with a desktop stand.

Once configured, the camera lives in the same Home tab inside the mobile app as any Philips Hue lights you've got. The main panel doesn't show the camera feed—instead, it shows the armed status of the camera, which can be configured separately depending on whether you're at home or not. The idea is that you don't get disturbed with a flurry of unnecessary notifications when you're moving around.

The basic functionality is the same as every other security camera: Motion is detected and you get a ping to your phone with details, with a saved clip of the event that stays available for 24 hours. You can also tap into the live feed from the camera at any time, should you want to check in on the pets or the backyard.

As is often the case with security cameras, there is an optional subscription plan that gives you long-term video clip storage, activity zone settings, and AI-powered identification of people, animals, vehicles, and packages. That will set you back from $4 a month, with a discount if you pay for a year at a time.

I started off a little unsure about just how useful it would be to connect up the Hue cameras and Hue lights—it's not a combination that gets talked about much—but it's surprisingly useful. If you delve into the camera settings inside the Hue app, there's a Trigger lights section especially for this.

You get to choose which of your lights are affected—they don't all have to go on and off together—and there are customizations for color and brightness across certain time schedules. You could have your bulbs glowing red during the night, for example, or turning bright blue during the daytime. The duration the lights stay on for can also be set.

It's not the most sophisticated system, but it works: If someone is loitering around your property, you can have a selected number of lights turn on to put them off, or to suggest that someone is in fact at home. This is in addition to everything else you can do, including sounding a siren through the camera, and because it works through the Hue Bridge it all happens pretty much instantaneously.

You can also set specific cameras as basic motion sensors for you and your family—lighting up the way to the bathroom late at night, for example. This can work even when the system is disarmed, so there's no wifi video streaming happening, but the cameras are still watching out for movement and responding accordingly.

There's one more option worth mentioning in the security settings in the Hue app: "mimic presence." This can randomly turn your lights on and off at certain points in the day, and the schedule you choose can be controlled by whether or not your Hue security is armed or disarmed (so nothing happens when everyone is at home).

In the corporate battle over parent company Warner Bros. Discovery, CNN's fate remains up for grabs. President Trump wants a say in what happens next.

(Image credit: Andrew Harnik)

© Risto Bozovic/Associated Press

OT oversight is an expensive industrial paradox. It’s hard to believe that an area can be simultaneously underappreciated, underfunded, and under increasing attack. And yet, with ransomware hackers knowing that downtime equals disaster and companies not monitoring in kind, this is an open and glaring hole across many ecosystems. Even a glance at the numbers..

The post Hacks Up, Budgets Down: OT Oversight Must Be An IT Priority appeared first on Security Boulevard.