U.S. Threatens Penalties Against European Tech Firms Amid Regulatory Fight

© Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times

© Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times

Just in time for Christmas, a little calf has arrived at a German zoo and gone viral. But is he cuter than Moo Deng?

Name: Panya the pygmy hippo.

Age: About three weeks.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Thilo Schmülgen/Reuters

© Photograph: Thilo Schmülgen/Reuters

© Photograph: Thilo Schmülgen/Reuters

Exclusive: David Dinsmore to advise ministers as they step up efforts to combat far-right rhetoric online

Keir Starmer’s Whitehall communications chief will address the cabinet on overhauling the government’s media strategy on Tuesday as ministers increasingly try to combat far-right rhetoric online.

David Dinsmore, a former editor of the Sun who was appointed permanent secretary for government communications in November, will speak to ministers about modernising the way they reach voters.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Sarah Lee/The Guardian

© Photograph: Sarah Lee/The Guardian

© Photograph: Sarah Lee/The Guardian

Like most tools, generative AI models can be misused. And when the misuse gets bad enough that a major dictionary notices, you know it has become a cultural phenomenon.

On Sunday, Merriam-Webster announced that “slop” is its 2025 Word of the Year, reflecting how the term has become shorthand for the flood of low-quality AI-generated content that has spread across social media, search results, and the web at large. The dictionary defines slop as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.”

“It’s such an illustrative word,” Merriam-Webster President Greg Barlow told The Associated Press. “It’s part of a transformative technology, AI, and it’s something that people have found fascinating, annoying, and a little bit ridiculous.”

Our investigation of the Free Birth Society points to problems with maternity care and the role played by technology

Despite all the proven advances of modern medicine, some people are drawn to alternative or “natural” cures and practices. Many of these do no harm. As the cancer specialist Prof Chris Pyke noted last year, people undergoing cancer treatment will often try meditation or vitamins as well. When such a change is in addition to, and not instead of, evidence-based treatment, this is usually not a problem. If it reduces distress, it can help.

But the proliferation of online health influencers poses challenges that governments and regulators in many countries have yet to grasp. The Guardian’s investigation into the Free Birth Society (FBS), a business offering membership and advice to expectant mothers, and training for “birth keepers”, has exposed 48 cases of late-term stillbirths or other serious harm involving mothers or birth attendants who appear to be linked to FBS. While the company is based in North Carolina, its reach is international. In the UK, the NHS only recently removed a webpage linking to a charity “factsheet” that recommended FBS materials.

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Oscar Wong/Getty Images

© Photograph: Oscar Wong/Getty Images

© Photograph: Oscar Wong/Getty Images

The long-running series in which readers answer other readers’ questions on subjects ranging from trivial flights of fancy to profound scientific and philosophical concepts

The dramatic chipmunk, distracted boyfriend, the raccoon with the candy floss or “success kid”, what is – or was – the absolute top, world-beating, best-ever internet meme? Antony Scacchi, Los Angeles, US

Post your answers (and new questions) below or send them to nq@theguardian.com. A selection will be published next Sunday.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Posed by models; Daniel de la Hoz/Getty Images

© Photograph: Posed by models; Daniel de la Hoz/Getty Images

© Photograph: Posed by models; Daniel de la Hoz/Getty Images

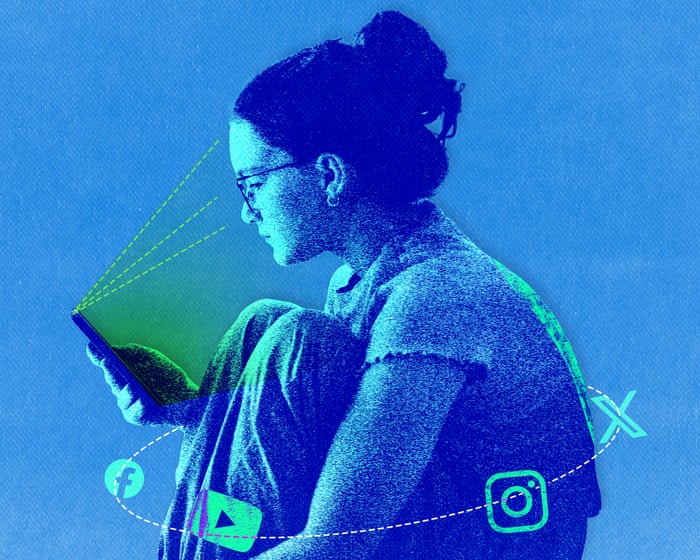

Australia is showing what is possible by not succumbing to the pressures of big tech. The UK needs to follow its lead, says Daniel Kebede

Lisa Nandy’s suggestion that an Australian-style restriction on social media for under-16s would lead to prosecuting children is a distraction (Young people have faced ‘violent indifference’ for decades, Lisa Nandy says, 9 December). No one is calling for teenagers to be criminalised for using platforms designed to keep them hooked. The responsibility lies squarely with the tech companies that profit from exposing children to harm. Why does the government still allow systems that erode childhood for commercial gain?

Teachers and parents witness the fallout daily: pupils too anxious and distracted to learn, children awake into the night because notifications demand constant attention, bullying that never ends, and content that pushes young people to extremes. This is not poor parenting or teaching – it is caused by the exploitative business models at the core of these addictive platforms.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Svetlana Akifyeva/Alamy

© Photograph: Svetlana Akifyeva/Alamy

© Photograph: Svetlana Akifyeva/Alamy

The potential demand that visitors to the US hand over their social media records, or even their phones, opens up a world of embarrassment

As someone with a child in the US, this new Trump threat to scrutinise tourists’ social media is concerning. Providing my user name would be OK – the authorities would get sick of scrolling through chicken pics before they found anything critical of their Glorious Leader – but what if I have to hand over my phone at the border, as has happened to some travellers already? I would rather get deported.

There’s nothing criminal or egregiously immoral on there; I don’t foment revolution or indulge in Trump trolling, tempting as that would be. But my phone does not paint a flattering picture of me. Does anyone’s? Those shiny black rectangles have become contemporary confessionals, and we would like to believe they abide by the same kind of confidentiality rules.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Posed by model; Drazen Zigic/Getty Images

© Photograph: Posed by model; Drazen Zigic/Getty Images

© Photograph: Posed by model; Drazen Zigic/Getty Images

Whether it’s nightclubs banning phones or a drop in online dating, there are signs that we’re rediscovering the joy of being in the moment

It’s only a small rectangular sticker, but it symbolises a joyous sense of resistance. Some of Berlin’s most renowned clubs have long insisted that the camera lenses on their clientele’s phones must be covered up using this simple method, to ensure that everyone is present in the moment and people can let go without fear of their image suddenly appearing on some online platform. As one DJ puts it, “Do you really want to be in someone’s picture in your jockstrap?”

Venues in London, Manchester and New York now enforce the same rules. Last week brought news of the return of Sankeys, the famous Mancunian club that closed nearly a decade ago, and is reopening in a 500-capacity space in the heart of the city. The aim, it seems, is to fly in the face of the massed closures of such venues, and revive the idea that our metropolises should host the kind of nights that stretch into the following morning. But there is another basic principle at work: phones will reportedly either be stickered or forbidden. “People need to stop taking pictures and start dancing to the beat,” said one of the club’s original founders.

John Harris is a Guardian columnist. His book Maybe I’m Amazed: A Story of Love and Connection in Ten Songs is available from the Guardian bookshop

Continue reading...

© Illustration: Nathalie Lees/The Guardian

© Illustration: Nathalie Lees/The Guardian

© Illustration: Nathalie Lees/The Guardian

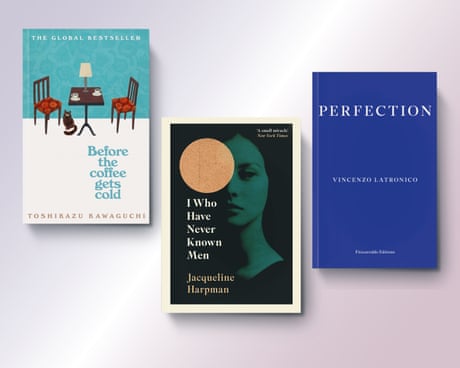

Whether it’s through TikTok buzz, celebrity endorsements or good old-fashioned word of mouth, some titles enjoy a second, more powerful, life. But what unites them – and is there a formula for this type of success?

There is a particular kind of literary deja vu that strikes sometimes. Seemingly out of nowhere, the same book starts appearing across multiple social media feeds. On the bus, you’ll spot two copies of the same title in one day. A friend says, “Have you read this yet?”, to which you respond, “Someone was just telling me about it the other day.”

These are the sleeper hits that seem to materialise without warning. They are not stacked high on the new release tables. They are books that, for one reason or another, have slipped their original timelines and found a second, often more powerful life.

Continue reading...

© Composite: N/A

© Composite: N/A

© Composite: N/A

The ban on under-16s accessing ‘harmful’ content that began this week has overwhelming approval from adults – even if it had a few teething issues

A few weeks ago, my 14-year-old went into the garage, pulled out his skateboard and told me this was going to be his “skate park summer”. I was curious about what was sparking his renewed interest in an activity he hadn’t thought about since he was 12. His response: “The ban.”

I was thrilled. As far as I was concerned, Australia’s world-first social media law aimed at preventing children under 16 from accessing social media apps was already a success. But this week, as the ban took effect, my son wasn’t so sure. Access to his accounts remained largely unchanged. Many of his friends were in the same position. Across the country, the rollout has been uneven, as social media companies try to work out how to verify kids’ ages.

Sisonke Msimang is the author of Always Another Country: A Memoir of Exile and Home (2017) and The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela (2018)

Continue reading...

© Illustration: Eiko Ojala/The Guardian

© Illustration: Eiko Ojala/The Guardian

© Illustration: Eiko Ojala/The Guardian

Several European nations are already planning similar moves while Britain has said ‘nothing is off the table’

Australia is taking on powerful tech companies with its under-16 social media ban, but will the rest of the world follow? The country’s enactment of the policy is being watched closely by politicians, safety campaigners and parents. A number of other countries are not far behind, with Europe in particular hoping to replicate Australia, while the UK is keeping more of a watchful interest.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Saeed Khan/AFP/Getty Images

© Photograph: Saeed Khan/AFP/Getty Images

© Photograph: Saeed Khan/AFP/Getty Images

The PM’s social media sortie has not been a total embarrassment, which may be a shame for him

The scene opens on the interior of an aeroplane.

A suited man in a luxurious seat looks pensively out the window, his face partially obscured, his chin delicately resting on his hand.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: TikTok

© Photograph: TikTok

© Photograph: TikTok

© Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times

© Photo Illustration by The New York Times; Photo: David Gray/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The policy to cut off social media access for more than 2 million under-16s remains popular with Australians, while other countries look to follow suit

On the lawns of the prime minister’s Kirribilli residence in Sydney, overlooking the harbour, Anthony Albanese said he had never been prouder.

“This is a day in which my pride to be prime minister of Australia has never been greater. This is world-leading. This is Australia showing enough is enough,” he said as the country’s under-16s social media ban came into effect on Wednesday.

Continue reading...

© Composite: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design/Getty images

© Composite: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design/Getty images

© Composite: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design/Getty images

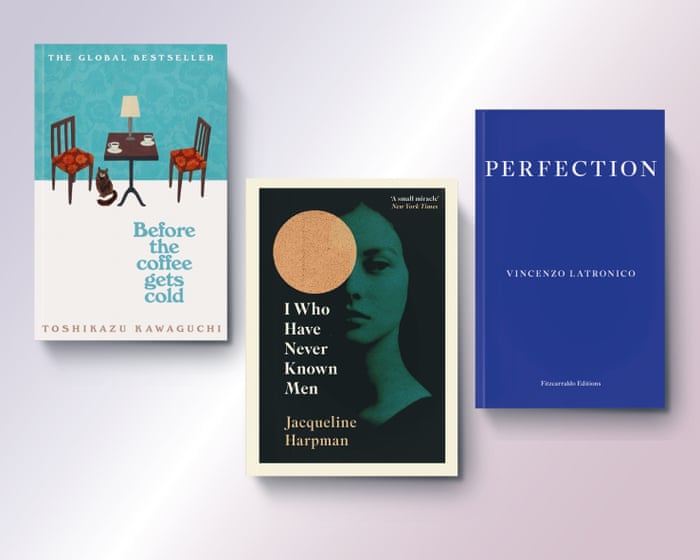

Platform fighting world-leading ban on grounds it contravenes implied freedom of political communication in constitution

Reddit has filed a challenge against Australia’s under-16s social media ban in the high court, lodging its case two days after implementing age restrictions on its website.

The company said in a Reddit post on Friday that while it agreed with protecting people under 16, the law “has the unfortunate effect of forcing intrusive and potentially insecure verification processes on adults as well as minors, isolating teens from the ability to engage in age-appropriate community experiences”.

Reddit said there was an “illogical patchwork” of platforms included in the ban.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: AAP

© Photograph: AAP

© Photograph: AAP

© Ida Marie Odgaard/Ritzau Scanpix, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Some warn proposal will decimate US tourism industry as free speech advocates say it will lead to people self-censoring

Free speech advocates have accused Donald Trump of “shredding civil liberties” and “censorship pure and simple” after the White House said it planned to require visa applicants from dozens of countries to provide social media, phone and email histories for vetting before being allowed into the US.

In a move that some commentators compared to China and others warned would decimate tourism to the US, including the 2026 Fifa World Cup, the Department for Homeland Security said it was planning to apply the rules to visitors from 42 countries, including the UK, Ireland, Australia, France, Germany and Japan, if they want to enter the US on the commonly used Esta visa waiver.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: NurPhoto/Getty Images

© Photograph: NurPhoto/Getty Images

© Photograph: NurPhoto/Getty Images

Figures for England and Wales show there were 51,672 offences for child sexual exploitation and abuse online in 2024

Online child sexual abuse in England and Wales has surged by a quarter within a year, figures show, prompting police to call for social media platforms to do more to protect young people.

Becky Riggs, the acting chief constable of Staffordshire police, called for tech companies to use AI tools to automatically prevent indecent pictures from being uploaded and shared on their sites.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Fiordaliso/Getty Images

© Photograph: Fiordaliso/Getty Images

© Photograph: Fiordaliso/Getty Images

If search interest holds, glitchy glam, cool blue, aliencore and gummy bear aesthetics are among the vibes set to rock the creative world next year

Next year, we’ll mostly be indulging in maximalist circus decor, working on our poetcore, hunting for the ethereal or eating cabbage in a bid for “individuality and self-preservation”, according to Pinterest.

The organisation’s predictions for Australian trends in 2026 have landed, which – according to the platform used by interior decorators, fashion lovers and creatives of all stripes – includes 1980s, aliens, vampires and “forest magic”.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: SeventyFour/Getty Images

© Photograph: SeventyFour/Getty Images

© Photograph: SeventyFour/Getty Images

The platform’s esoteric watchlists and rating system appeal to cinephiles craving a different mode of discovery

I never thought I would use Letterboxd. The app’s premise of logging reviews of every film you watch felt like counting steps, and I generally prefer to exercise my pretension the old fashioned way – such as getting a BFA or frequenting art house cinema screenings where I am usually the only person under 50 in the theater.

But after I wrote about my feelgood movie for the Guardian – that would be Sullivan’s Travels, Preston Sturges’s perfect 1941 satire – I was swayed by two newsroom colleagues. “Hey Alaina, we heard you like movies,” one of them said. “What’s your Letterboxd?” I wanted to be part of the club, and signed up later that night. Now, I write thoughts on every movie I see, usually before I’ve even left the theater or closed out the streamer.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: letterboxd

© Photograph: letterboxd

© Photograph: letterboxd

Plan would apply to countries not currently required to get visas to the US, including Britain and France

Tourists to the United States would have to reveal their social media activity from the last five years, under new Trump administration plans.

The mandatory new disclosures would apply to the 42 countries whose nationals are currently permitted to enter the US without a visa, including longtime US allies Britain, France, Australia, Germany and Japan.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Jeff Greenberg/Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

© Photograph: Jeff Greenberg/Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

© Photograph: Jeff Greenberg/Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

We asked you to share your views on your children’s use of social media and how the ban is affecting your family. Here is what you told us

For some parents, social media sucks up their children’s time and steals them away from family life, instilling mental health issues along the way. For others, it provides their children with an essential line to friends, family, connection and support.

When Australia’s social media ban came into effect on Wednesday, millions of under-16s lost access to their accounts and were prevented from creating new ones.

Continue reading...

© Composite: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design

© Composite: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design

© Composite: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design

Source: eSafety Commissioner[/caption]

Source: eSafety Commissioner[/caption]

Source: Created using Google Gemini[/caption]

Research supports these concerns. A Pew Research Center study found:

Source: Created using Google Gemini[/caption]

Research supports these concerns. A Pew Research Center study found:

“The social media ban only really addresses on set of risks for young people, which is algorithmic amplification of inappropriate content and the doomscrolling or infinite scroll. Many risks remain. The ban does nothing to address cyberbullying since messaging platforms are exempt from the ban, so cyberbullying will simply shift from one platform to another.”

Leaver also noted that restricting access to popular platforms will not drive children offline. Due to ban on social media young users will explore whatever digital spaces remain, which could be less regulated and potentially riskier.

“Young people are not leaving the digital world. If we take some apps and platforms away, they will explore and experiment with whatever is left. If those remaining spaces are less known and more risky, then the risks for young people could definitely increase. Ideally the ban will lead to more conversations with parents and others about what young people explore and do online, which could mitigate many of the risks.”

From a broader perspective, Leaver emphasized that the ban on social media will only be fully beneficial if accompanied by significant investment in digital literacy and digital citizenship programs across schools:

“The only way this ban could be fully beneficial is if there is a huge increase in funding and delivery of digital literacy and digital citizenship programs across the whole K-12 educational spectrum. We have to formally teach young people those literacies they might otherwise have learnt socially, otherwise the ban is just a 3 year wait that achieves nothing.”

He added that platforms themselves should take a proactive role in protecting children:

“There is a global appetite for better regulation of platforms, especially regarding children and young people. A digital duty of care which requires platforms to examine and proactively reduce or mitigate risks before they appear on platforms would be ideal, and is something Australia and other countries are exploring. Minimizing risks before they occur would be vastly preferable to the current processes which can only usually address harm once it occurs.”

Looking at the global stage, Leaver sees Australia ban on social media as a potential learning opportunity for other nations:

“There is clearly global appetite for better and more meaningful regulation of digital platforms. For countries considered their own bans, taking the time to really examine the rollout in Australia, to learn from our mistakes as much as our ambitions, would seem the most sensible path forward.”

Other specialists continue to warn that the ban on social media could isolate vulnerable teenagers or push them toward more dangerous, unregulated corners of the internet.

© Mikel Jaso

The chancellor will give evidence to the Commons Treasury committee about the budget from 10am

Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, will start giving evidence to the Treasury committee at 10am. She will appear alongside James Bowler, permanent secretary at the Treasury, and Dharmesh Nayee, its director of strategy, planning and budget.

This is what the Treasury committee said in a news release about the topics it wants to cover.

Members are likely to examine the significant changes to the Treasury’s tax and spending plans, and potential implications for the economy, public services and government debt.

The chancellor is also expected to answer questions on topical issues, such as how her department handled the months leading up to the budget and the recently announced leak inquiry.

It’s our generation’s responsibility to break down barriers to opportunity for young people.

We’re investing in youth services so every child has the chance to thrive and we’re boosting apprenticeships so young people can see their talents take them as far as they can.

-Build or refurbish up to 250 youth facilities over the next four years, as well as providing equipment for activities to around 2,500 youth organisations, through a new £350m ‘Better Youth Spaces’ programme. It will provide safe and welcoming spaces, offering young people somewhere to go, something meaningful to do, and someone who cares about their wellbeing.

-Launch a network of 50 Young Futures Hubs by March 2029 as part of a local transformation programme of £70m, providing access to youth workers and other professionals, supporting their wellbeing and career development and preventing them from harm.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Anadolu/Getty Images

© Photograph: Anadolu/Getty Images

© Photograph: Anadolu/Getty Images

Does Australia’s social media ban mean kids aged under 16 will get in legal trouble for circumventing the ban? Will parents get in trouble for letting their kids use banned social media sites? There is a lot of misinformation about how the world-first ban will actually work. So whether you’re a parent of a child, or a child watching this on a VPN, Guardian Australia’s Matilda Boseley is here to clear up what the social media ban means

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Guardian Design

© Photograph: Guardian Design

© Photograph: Guardian Design

© Getty Images

© Illustration: Ben Jennings/The Guardian

© Illustration: Ben Jennings/The Guardian

© Illustration: Ben Jennings/The Guardian

Our UN report reveals the link between the online misogyny and offline crimes that are hounding women out of public life

Networked misogyny is now firmly established as a key tactic in the 21st-century authoritarian’s playbook. This is not a new trend – but it is now being supercharged by generative AI tools that make it easier, quicker and cheaper than ever to perpetrate online violence against women in public life – from journalists to human rights defenders, politicians and activists.

The objectives are clear: to help justify the rollback of gender equality and women’s reproductive rights; to chill women’s freedom of expression and their participation in democratic deliberation; to discredit truth-tellers; and to pave the way for the consolidation of authoritarian power.

Dr Julie Posetti is the director of the Information Integrity Initiative at TheNerve, a digital forensics lab founded by Nobel laureate Maria Ressa. She is also a professor of journalism and chair of the Centre for Journalism and Democracy at City St George’s, University of London.

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Guglielmo Mangiapane/Reuters

© Photograph: Guglielmo Mangiapane/Reuters

© Photograph: Guglielmo Mangiapane/Reuters

Accounts held by users under 16 must be removed on apps that include TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, X, YouTube, Snapchat, Reddit, Kick, Twitch and Threads under ban

Australia has enacted a world-first ban on social media for users aged under 16, causing millions of children and teenagers to lose access to their accounts.

Facebook, Instagram, Threads, X, YouTube, Snapchat, Reddit, Kick, Twitch and TikTok are expected to have taken steps from Wednesday to remove accounts held by users under 16 years of age in Australia, and prevent those teens from registering new accounts.

Continue reading...

© Illustration: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design/Getty Images

© Illustration: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design/Getty Images

© Illustration: Victoria Hart/Guardian Design/Getty Images

© Philip Cheung for The New York Times

© The New York Times

As midlife audiences turn to digital media, the 55 to 64 age bracket is an increasingly important demographic

In 2022, Caroline Idiens was on holiday halfway up an Italian mountain when her brother called to tell her to check her Instagram account. “I said, ‘I haven’t got any wifi. And he said: ‘Every time you refresh, it’s adding 500 followers.’ So I had to try to get to the top of the hill with the phone to check for myself.”

A personal trainer from Berkshire who began posting her fitness classes online at the start of lockdown in 2020, Idiens, 53, had already built a respectable following.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Elena Sigtryggsson

© Photograph: Elena Sigtryggsson

© Photograph: Elena Sigtryggsson

Exclusive: Guardian investigation finds fake agencies using the social media platform to dupe Kenyans into paying for nonexistent jobs in Europe

Lilian, a 35-year-old Kenyan living in Qatar, was scrolling on TikTok in April when she saw posts from a recruitment agency offering jobs overseas. The Kenya-based WorldPath House of Travel, with more than 20,000 followers on the social media platform, promised hassle-free work visas for jobs across Europe.

“They were showing work permits they’d received, envelopes, like: ‘We have Europe visas already,’” Lilian recalls.

Continue reading...

© Illustration: Getty Images/Guardian pictures

© Illustration: Getty Images/Guardian pictures

© Illustration: Getty Images/Guardian pictures

© Irena Rudovska/iStock; Thomas Fuller/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images; Illustration by The New York Times

© William West/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times

© Jim Wilson/The New York Times

In his 2020 book, “Future Politics,” British barrister Jamie Susskind wrote that the dominant question of the 20th century was “How much of our collective life should be determined by the state, and what should be left to the market and civil society?” But in the early decades of this century, Susskind suggested that we face a different question: “To what extent should our lives be directed and controlled by powerful digital systems—and on what terms?”

Artificial intelligence (AI) forces us to confront this question. It is a technology that in theory amplifies the power of its users: A manager, marketer, political campaigner, or opinionated internet user can utter a single instruction, and see their message—whatever it is—instantly written, personalized, and propagated via email, text, social, or other channels to thousands of people within their organization, or millions around the world. It also allows us to individualize solicitations for political donations, elaborate a grievance into a well-articulated policy position, or tailor a persuasive argument to an identity group, or even a single person.

But even as it offers endless potential, AI is a technology that—like the state—gives others new powers to control our lives and experiences.

We’ve seen this play out before. Social media companies made the same sorts of promises 20 years ago: instant communication enabling individual connection at massive scale. Fast-forward to today, and the technology that was supposed to give individuals power and influence ended up controlling us. Today social media dominates our time and attention, assaults our mental health, and—together with its Big Tech parent companies—captures an unfathomable fraction of our economy, even as it poses risks to our democracy.

The novelty and potential of social media was as present then as it is for AI now, which should make us wary of its potential harmful consequences for society and democracy. We legitimately fear artificial voices and manufactured reality drowning out real people on the internet: on social media, in chat rooms, everywhere we might try to connect with others.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Alongside these evident risks, AI has legitimate potential to transform both everyday life and democratic governance in positive ways. In our new book, “Rewiring Democracy,” we chronicle examples from around the globe of democracies using AI to make regulatory enforcement more efficient, catch tax cheats, speed up judicial processes, synthesize input from constituents to legislatures, and much more. Because democracies distribute power across institutions and individuals, making the right choices about how to shape AI and its uses requires both clarity and alignment across society.

To that end, we spotlight four pivotal choices facing private and public actors. These choices are similar to those we faced during the advent of social media, and in retrospect we can see that we made the wrong decisions back then. Our collective choices in 2025—choices made by tech CEOs, politicians, and citizens alike—may dictate whether AI is applied to positive and pro-democratic, or harmful and civically destructive, ends.

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) calls it fraud when a candidate hires an actor to impersonate their opponent. More recently, they had to decide whether doing the same thing with an AI deepfake makes it okay. (They concluded it does not.) Although in this case the FEC made the right decision, this is just one example of how AIs could skirt laws that govern people.

Likewise, courts are having to decide if and when it is okay for an AI to reuse creative materials without compensation or attribution, which might constitute plagiarism or copyright infringement if carried out by a human. (The court outcomes so far are mixed.) Courts are also adjudicating whether corporations are responsible for upholding promises made by AI customer service representatives. (In the case of Air Canada, the answer was yes, and insurers have started covering the liability.)

Social media companies faced many of the same hazards decades ago and have largely been shielded by the combination of Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1994 and the safe harbor offered by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998. Even in the absence of congressional action to strengthen or add rigor to this law, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Supreme Court could take action to enhance its effects and to clarify which humans are responsible when technology is used, in effect, to bypass existing law.

As AI-enabled products increasingly ask Americans to share yet more of their personal information—their “context“—to use digital services like personal assistants, safeguarding the interests of the American consumer should be a bipartisan cause in Congress.

It has been nearly 10 years since Europe adopted comprehensive data privacy regulation. Today, American companies exert massive efforts to limit data collection, acquire consent for use of data, and hold it confidential under significant financial penalties—but only for their customers and users in the EU.

Regardless, a decade later the U.S. has still failed to make progress on any serious attempts at comprehensive federal privacy legislation written for the 21st century, and there are precious few data privacy protections that apply to narrow slices of the economy and population. This inaction comes in spite of scandal after scandal regarding Big Tech corporations’ irresponsible and harmful use of our personal data: Oracle’s data profiling, Facebook and Cambridge Analytica, Google ignoring data privacy opt-out requests, and many more.

Privacy is just one side of the obligations AI companies should have with respect to our data; the other side is portability—that is, the ability for individuals to choose to migrate and share their data between consumer tools and technology systems. To the extent that knowing our personal context really does enable better and more personalized AI services, it’s critical that consumers have the ability to extract and migrate their personal context between AI solutions. Consumers should own their own data, and with that ownership should come explicit control over who and what platforms it is shared with, as well as withheld from. Regulators could mandate this interoperability. Otherwise, users are locked in and lack freedom of choice between competing AI solutions—much like the time invested to build a following on a social network has locked many users to those platforms.

It has become increasingly clear that social media is not a town square in the utopian sense of an open and protected public forum where political ideas are distributed and debated in good faith. If anything, social media has coarsened and degraded our public discourse. Meanwhile, the sole act of Congress designed to substantially reign in the social and political effects of social media platforms—the TikTok ban, which aimed to protect the American public from Chinese influence and data collection, citing it as a national security threat—is one it seems to no longer even acknowledge.

While Congress has waffled, regulation in the U.S. is happening at the state level. Several states have limited children’s and teens’ access to social media. With Congress having rejected—for now—a threatened federal moratorium on state-level regulation of AI, California passed a new slate of AI regulations after mollifying a lobbying onslaught from industry opponents. Perhaps most interesting, Maryland has recently become the first in the nation to levy taxes on digital advertising platform companies.

States now face a choice of whether to apply a similar reparative tax to AI companies to recapture a fraction of the costs they externalize on the public to fund affected public services. State legislators concerned with the potential loss of jobs, cheating in schools, and harm to those with mental health concerns caused by AI have options to combat it. They could extract the funding needed to mitigate these harms to support public services—strengthening job training programs and public employment, public schools, public health services, even public media and technology.

A pivotal moment in the social media timeline occurred in 2006, when Facebook opened its service to the public after years of catering to students of select universities. Millions quickly signed up for a free service where the only source of monetization was the extraction of their attention and personal data.

Today, about half of Americans are daily users of AI, mostly via free products from Facebook’s parent company Meta and a handful of other familiar Big Tech giants and venture-backed tech firms such as Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Anthropic—with every incentive to follow the same path as the social platforms.

But now, as then, there are alternatives. Some nonprofit initiatives are building open-source AI tools that have transparent foundations and can be run locally and under users’ control, like AllenAI and EleutherAI. Some governments, like Singapore, Indonesia, and Switzerland, are building public alternatives to corporate AI that don’t suffer from the perverse incentives introduced by the profit motive of private entities.

Just as social media users have faced platform choices with a range of value propositions and ideological valences—as diverse as X, Bluesky, and Mastodon—the same will increasingly be true of AI. Those of us who use AI products in our everyday lives as people, workers, and citizens may not have the same power as judges, lawmakers, and state officials. But we can play a small role in influencing the broader AI ecosystem by demonstrating interest in and usage of these alternatives to Big AI. If you’re a regular user of commercial AI apps, consider trying the free-to-use service for Switzerland’s public Apertus model.

None of these choices are really new. They were all present almost 20 years ago, as social media moved from niche to mainstream. They were all policy debates we did not have, choosing instead to view these technologies through rose-colored glasses. Today, though, we can choose a different path and realize a different future. It is critical that we intentionally navigate a path to a positive future for societal use of AI—before the consolidation of power renders it too late to do so.

This post was written with Nathan E. Sanders, and originally appeared in Lawfare.

© Andre Penner/Associated Press

© Bee Trofort for The New York Times

© Andres Kudacki for The New York Times

© Victor Llorente for The New York Times

© Stefani Reynolds for The New York Times